Families Outside is a national Scottish charity working entirely on behalf of children and families affected by imprisonment. They offer support in three ways: direct emotional support, delivery of training and raising awareness, and longer-term development of policies and practices that create change. Joining Julia Lazareck today is the organization’s Chief Executive, Nancy Loucks, OBE. Nancy imparts their best practices that have helped many and paved the way for positive change in terms of treatment and support of prison families. There is much to learn how other countries and governments like Scotland create systems to help oversee the needs of these families. Tune in to find out more.

—

Listen to the podcast here

What We Can Learn From Scotland’s Families Outside With Nancy Loucks

I’m here with Professor Nancy Loucks, Chief Executive from Families Outside, based in Edinburgh, Scotland. We’re bringing her here to talk about the programs and successes of Families Outside. Here in the United States, we have some organizations like Prison Families Alliance that support families and children. However, we only don’t have organizations that have the relationship that Families Outside has with its government and we could learn a lot from them.

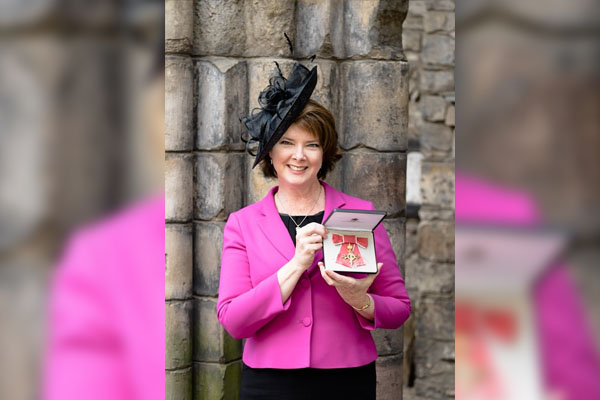

Nancy’s the Chief Executive of Families Outside and works tirelessly to ensure the voices of children and families affected by imprisonment are heard. Prior to Families Outside, she worked as an independent criminologist, specializing in research on prison policy and comparative criminology. She received her Master’s of Philosophy and PhD from the Institute of Criminology at the University of Cambridge. In 2012, she was appointed as Visiting Professor at the University of Strathclyde Center for Law, Crime and Justice.

She was awarded an OBE, which is the Officer of the British Empire in the 2015-2016 New Year’s Honors List for Services to Education and Human Rights. Nancy, thank you so much for being here. I’m excited to talk with you. I like to hear a little bit more about this Officer of the British Empire, the OBE Award that you received.

It’s the Officer of the British Empire, which is an award from the Queen. It’s one of a hierarchy of awards. It starts with the MBE and then goes up to the OBE, CBE, Knighthoods, and Damehoods. This didn’t involve any swords or anything like that. It’s a nomination. You don’t know who nominates you, but you have to write to the Queen’s people. I don’t know who they are. They are Royal households. They nominate you, then you’re selected based on that. It was exciting, especially as I’m originally from the US. It’s something that’s only bestowed on British citizens. It was quite exciting to be able to go to the Palace and have the Queen pin a medal on your suit and speak to you briefly about your work, then you move on. It’s a nice thing.

I have goosebumps. You have an award from the Queen. That’s why I bring it up. I thought that sounded so exciting. Let’s talk about what Families Outside does, all the wonderful work that you’re doing.

Families Outside is a national Scottish charity. We work entirely on behalf of children and families affected by imprisonment. Similar to yourselves, it’s a single issue, but it cuts across so many different areas. Prison impacts so many different parts of people’s lives. We try to support families in three different ways. One is that direct support and providing that practical information, advice, emotional support, anything that the family needs. One of the biggest parts of our work is direct support to families. We can do that in person, through a helpline, online or whatever the family feels most comfortable with.

The second part is delivery of training and awareness-raising sessions. We’re trying to raise awareness about the impact of stigma in that way but also making sure that by training social workers, teachers, health professionals, prison staff and all of these people that they will themselves be able to provide support and reduce the judgments that family seem to face much of the time. It widens the network of support to families through that training and awareness-raising.

The third part of our work is the longer-term work. It’s the development of policy and practice that creates longer-term change to make sure that families aren’t facing the same barriers that they might be at that time. That’s a longer-term focus, I suppose. In that sense, we don’t have a program of support. We don’t say, “We provide this particular service for twelve weeks and it’s done.” It’s whatever the family needs and helps them because each one faces different challenges. They have different supports, facing different circumstances. It’s making sure that we do what needs to be done, whatever that might be. That hopefully summarizes what we do.

Could you give an example of a family, like a process? At some point, I’d like to talk about the visiting center if it fits in here later. Give us an example of a family that’s come to you in what you’ve done.

As an example, there was one case that would be used as a case study. It was a teacher who took part in a training session that we ran. One of the popular training sessions that we do is we take teachers in prison to experience what a visit is like. They go through all the searching procedures and so on, then we hold the training workshop in the prison visits hall. That’s quite good. The teacher took part in this particular piece of training, went back to their school and put some leaflets in the staff room and posters up around the school.

Each family is facing different challenges. They have different supports, facing different circumstances so we make sure that we do what needs to be done, whatever that may be. Share on XAs a result, he came across a young boy who was struggling in school. His behavior began to deteriorate. The teacher was aware that prison might be one of the issues that they were dealing with. I spoke to them about that. It turns out that his dad had gone to prison and he wasn’t able to speak to his daddy. He hadn’t been able to visit. The child was at the stage where he was struggling in school and having to make some choices about subjects, teachers, all that thing. He wants to talk to his dad and he can’t do it. The teacher spoke to him about that he had been to the prison and spoke to the little boy’s mom to demystify what prison visits were like. I managed to arrange a video call with his dad to the prison, just as an introduction to that.

It was something that you’re dealing with a boy who was beginning to struggle, emotionally was suffering, who could have been causing problems in terms of being excluded from the school, being expelled. Instead, they turned it around because they became aware of what the issues were and what support this young boy might need. As a result, he was able to visit his dads. He was able to gain that contact and is doing well because he knew that he had people who could support him and understand the situation. That’s a fairly typical example of the types of things that having that awareness can make a difference.

If that teacher hadn’t gone to your organization’s training, the teacher wouldn’t have known what to look for and how to help the little boy. Imagine how wonderful he could speak to his daddy and understand the process. Let’s not be worried because kids worry. They keep it inside them.

Supporting the mom as well because the families do not like to jump up and down and say, “This is the issue that they’re facing.” There is a huge stigma, so they don’t come forward for support. To have someone else come to them and offer that support and know that they weren’t being judged. They were being supported helped in practical ways and it made a huge difference to the whole family as a result, and hopefully, to this little boy’s whole life. Recognizing school as a place for support and compassion, as opposed to judgment and exclusion.

You had it in the school and the little boy found out about it because of the teacher. How would his mother have found out about it?

In speaking to the little boy, the teacher said, “I want to talk to your mom about this. Is that okay?” The teacher reached out to the mom and was able to speak to her. That way, she didn’t have to come forward herself. She didn’t have to tell anybody else that she might not be comfortable talking with it. Having that approach of understanding and information can make a huge difference. They weren’t being identified or labeled or a big spotlight or fanfare. It was that practical, compassionate approach.

I have two questions. If the teacher hadn’t taken the class and the little boy didn’t know about it, how would his mother have found out about Families Outside to get support?

It’s an interesting question because it’s one that we struggle with quite a lot. Certainly, in terms of contact to our helpline, most people find us online, which is great, but not everybody has that confidence with using a computer or using the internet or access to the internet. A lot of people would find out about us at a prison visit. For example, there might be a poster or something but not everybody visits, especially if there’s an issue of distance or an issue of cost. You might not get people visiting a prison. In fact, when people go to prison, certainly in Scotland, only about half of the people in prison receive visits. That can be a real problem as well. We can’t expect the prison to be the place where people find out who we are.

That’s why we started reaching out to schools, doctors, social work teams, anywhere that would be available in the public where families in the situation might go, but it is difficult. Sometimes it does take people at these key professionals to reach out to them, to let people know that services like this exist. It can be quite tricky.

We have people coming to our support meetings and they’re like, “I wish I found you in the beginning.” If you can help people in the very beginning through the process, but that’s how they find us too.

We did try going to the courts, sitting in courts and trying to raise awareness that way, but it was so difficult to tell who the families were. Often, families weren’t in court. It might be some but not all. We set up a stall in the courts and we only reached about two families over a period of months doing that. Otherwise, they were asking for directions to the restroom or directions to the court. That wasn’t the best use of time. It is a constant experiment trying to find different ways to reach out to families who are not ones to draw themselves.

I always thought it might be good to have an office in the court and the attorneys know about it, so if somebody is taken into the system, then the families can go to this office and get information because they don’t know when they can visit. There are a lot of similarities even though it’s different countries, but still, the feelings are the same. Having that support is important.

We are trying to train the lawyers as well. We’re trying to encourage them to come to our trainings. That’s a slow process, but we’re getting there.

I wanted to get your thoughts. In the States here, some programs for children of incarcerated parents that are in the schools, we don’t have one here. We’re looking at how we can help the children here. How do they have these classes without causing stigma?

It’s not just about having visits. It’s about having good quality, meaningful, and relaxed visits. Share on XThat is an interesting question because we have done some workshops in schools where we would go to the school and they say, “We don’t have anyone here in that situation.” I remember one particular school. We did ten workshops over the course of the day. In every single one, a child came forward to say that they had a family member in prison and the school had never known. The children didn’t know about each other either. It was a real eye-opener. It is challenging sometimes too. You have to start up things like programs in school when the school doesn’t think that they need it. It’s only once you’re there that they realize that this is a real issue for the children there that they’re supporting. It’s quite a constant experiment.

There are so many programs that you have that I think would be great to be replicated here in the States. I want to take some of your training, even though it would be like 1:00 in the morning here. I still think I’m going to sign up because there are so many things that you’re doing that if we could get it into the schools and we could get people trained to have it like a training program. We’re learning from you.

Other things I wanted to mention as well were about prison visits are quite different over here as well. I’m from California originally. I have learned a lot about what things were like in the US then have come over here and tried to recognize what the differences are. One of them is about the prison visits situation. They are rarely through glass. For example, we only introduced video calls or visits because those didn’t exist until the pandemic. One of the benefits of a pandemic is having that option for family contact. It has been seen very much as an additional form of contact. One of the things that are happening in the prisons in Scotland is prison visitor centers. You see them in England and Wales,

In Scotland, they’re independently run places for people visiting prisons to go before or after a visit to get some information and support, have a coffee, relax, and unwind a bit before the visit. They might be able to access different types of services there, for example, certainly the criteria in Scotland, the requirement in Scotland for them to run by independent organizations. We found, for example, that some of the visitor centers in England were run by the prison. It completely changed the context and the purpose. I did a piece of research years ago on prison visitor centers. One of the first questions that I asked was the purpose of the visitor center.

Without knowing anything about who was running the center, I could tell who ran the center by how they answered that question. For prison visitor centers that were independent, it was about providing support, a cup of tea, a listening ear, writing information, making sure that families are connected and they’re relaxed to have a good quality meaningful visit. One of the prisons responded to that question by saying, “A master room for visitors to assemble so they can be processed quickly and efficiently.” I said, “You’ve got to be kidding me.”

It’s very important, but independence is extremely important to have a place because prison visiting is stressful. Having a place where people can go and gather their thoughts, leave their belongings if they have been traveling a long time, getting a cup of tea and stop at the restroom or something. To have that space, where again, they’re not judged. They’re supported and they can go in and have the best quality they can. That’s one of the things that we do and coordinate the work of all the prisoners centers in Scotland to make sure that they meet minimum standards so families have a basic level of support they can expect every time they go.

I remember visiting my brother and waiting outside. Everybody gets out early, so they can spend as much time with their loved ones. It could be raining. It could be the weather and climate. With my mother, luckily, there was one bench, so she got to sit down, but you’re standing out there. The thought of having a visiting center, someplace where you could go because it’s so stressful, to have somebody to talk to and laugh, especially if it’s your first time to have somebody walk you through the process.

When I heard about these visiting centers, I thought that it would be so wonderful if we could get somebody here in the States to at least try it and see how it works. The families would be more relaxed when they go to see their loved ones too. It’s a win-win where they can spend quality time. A place to leave your stuff, a meeting, especially if you have little ones.

They will have play areas and children’s workers and all that thing as well. It does make a huge shift. You know Dr. Yvonne Heart Johnson. I met her when she came over here to do some research on prison visitors at visitor centers and prison visiting. It was great to see her response or her reaction to visiting a center for the first time and seeing the difference that it made. She has published that. That was great to be able to see that.

She’s done a lot of work. She’s with the International Prisoners Family Conference advocacy and action and also INCCIP.

The International Coalition for Children with Incarcerated Parents. She’s the Vice-Chair of that. She’s involved in the Arizona Conference. I don’t know what she’s not involved in.

There are a lot of organizations out there like INCCIP and the ASU, Arizona State University. Organizations that specifically focus on children of incarcerated parents but are friendly. There are a lot of resources out there, here, international organizations, but that are also active here. In the beginning, you spoke about support for families. If you could walk us through maybe a family that you’ve worked with and how it’s benefited them.

There are so many examples. I mentioned the boy in school before. Most of the people that we work with interestingly are either parents of people in prison or partners of people in prison. The children are not necessarily the main client, if that makes sense, our main beneficiary. It is often people who face some incredibly difficult circumstances. There’s a lady, in fact, I’m still in touch with her, whose son is serving a life sentence. I remember her case vividly because her son’s offense came about. There was a party in her house. Her son was living with her at the time.

An argument broke out and it resulted in a death, which is incredibly distressing in itself, but because it was her house, her house was then a crime scene. She couldn’t go back to her house. She was homeless, literally, overnight. There was no place for her to go. She was incredibly distraught. As a result of the offense, her son split up with his partner, which meant that the lady we were supporting no longer had access to her grandchild. She became very mentally unwell and physically unwell as a result of being homeless and having the stress of her only child being locked away and having no access to her grandchild and lost her job on the back of all of that.

Your children have rights themselves. One of those is the right to contact with their parents. Share on XIt was one thing after another. We’ve been trying to help her back up again, build her back up, try to support her, try to find the health support that she needed, try to make sure that she has accommodation again, and make sure she has the social support she had. She starts a new job, which is great. It’s one of those things that can take years. I’ve been working with her. Her son is serving a life sentence. Every single stage is an adjustment to her in terms of what his situation is. COVID was a real nightmare because people were very worried about what the situation was for their families in prison during COVID.

She’s still having a battle for access to her grandchild because the partners are now estranged and don’t want anything to do with the family. It’s taking each family’s circumstances as they come. It’s another situation. This is probably more of an issue over here in relation to deportation because of Europe. There are a lot of very small countries, but it means that if someone comes from another country and they commit an offense or are imprisoned over here, then their automatically deported. The family might be stuck in one country with the person who’s been deported stuck in another one.

We had a case where the family was living in Spain. The man came here and got into trouble. It’s fairly minor. I don’t think he was in prison for more than a few months, but his birth passport was Austria. They were going to deport him back to Austria, even though he hadn’t lived there since he was a child, rather than sending him back to Spain, where his entire family was. Dealing with the logistics of trying to reunite families, even after a fairly short period in prison, can take a lot of sorting out, to say the least, and trying to help families navigate an entirely alien system and often more than one system.

In fact, we have a chart that we use, which talks about prisoners’ families in the middle of this, basically an octopus. The legs of the octopus are things like the justice system, housing, physical and mental health, transport and finances. There are all these different things. They’re all dealt with different systems and processes. It can get complex quickly and completely overwhelming for families who are dealing with the stress of having someone in prison than with everything else on top.

We have something similar. There isn’t as much travel, but in our federal system, somebody can be put in any state or even Hawaii and people are like, “Hawaii. It’ll be nice to go out there. They’re going to be with their loved one in there.” If they’re sent to a federal prison in Hawaii, it gets very expensive. That was the only thing I could relate to. Maybe it’s a similar situation here because that’s difficult. Helping families here to go see their loved ones when it’s far. We are working with another organization to help provide some travel help.

That is one thing we do have here. There are a lot of things I take for granted here in terms of government support. There is a government funding scheme called Help with Prison Visits, where if you put people on social welfare benefits, they can have the travel costs covered to get to prison. It’s not terribly generous, but it’s two visits a month. It can include overnight stays if need be, but it’s an option.

Health care here is covered. We don’t have things like if people are on sick leave or something from their work that there’s funding support for that as well. There are a lot of things like that, which do help families but take for granted now. I realize that this doesn’t exist in many places in the States, but we still have working families who are still living in poverty. That’s a real concern and a longer-term issue than we can address. I know a lot of my staff get frustrated when the issues that families are facing are much longer-term than we can fix.

You do have a relationship with the government. That’s something that we don’t have. Maybe you could talk a little bit about that relationship.

It’s one thing that is very fortunate about Scotland as a country. We even see benefits to this as opposed to England, which is a much larger country. Anything in England is about ten times the size of what we have here in Scotland, the religious 10% slice. In Scotland, if the prison services have imposed restrictions on something or if the government does something that isn’t recognizing what this means for families of people in prison, then you can pick up the phone. You know who to speak to. It’s a very small country. We were saying that, to put things in context, the entire Scottish prison population is 8,000 people.

It’s a very different scale from anything that you’d be dealing with it in the US. We have fifteen prisons in total. These prisons are much smaller as well. What we do with our organization is make sure we have a member of staff assigned to each prison. Every prison has its name to Families Outside. One member of staff might be covering 2 or 3 prisons, but even so, you have a named person. They know the prison governor and the prison staff. They know where to go if something’s not working or not being done as it should.

We also have a prison inspection service in Scotland. There’s an independent inspector who inspects all the prisons in Scotland and imposes minimum standards and enforces those standards. You know who to go to if you have to complain about something or if something is unfair, then you have a way of fixing it. Not that it always works. There certainly have plenty of things that need fixing, but there’s a way of doing it for people who refer to Scotland as a village, and it is, which does make a huge difference to have those relationships.

I don’t see any reason why we couldn’t find a town or a state that would want to try this because having the family visit is good. I know that you know this. I only have to say it. It’s good for the person that’s incarcerated. They’re going to be a better, for lack of a better word, inmate. There’s going to be less trouble in the prisons. Keeping the family together is so important. What you guys are doing in Scotland should be replicated in other places. I would love to see it replicated. Maybe someday it will be.

It’s not just about having visits, but it’s having good quality visits and meaningful visits and relaxed visits. We have something called children’s visits as well, which are special visits where it’s usually with the child often with the other parent. We’ll come in, but it means that the person in prison can get up and run around and play games. It’s a much more relaxed visit, which makes such a huge difference rather than having someone sitting in a chair and not moving. It’s something that is essential.

It’s interesting because we had the director, the prison service, who said, “Children’s visits are not a privilege. They’re not something that can be revoked unless someone uses a child to bring drugs into the prison or something.” Children’s visits are the right of the child. They can’t be taken away as punishment, for example. That’s something they are beginning to recognize now, particularly with the UN Convention. The children have rights themselves. One of those rights is the right to contact with your parents. That’s something we’re beginning to see happening in practice, which is so important.

It’s eye-opening to see how other people address the same types of problems, and to see your own country from the outside is enlightening. Share on XThat’s something that I learned about when I went to the INCCIP Conference, the UN Convention on the Rights of Children. Could you talk a little bit about that? That was something that was new to me.

It’s interesting and I still don’t understand why but the United States is the only member of the UN that hasn’t signed up to it, which is a mystery to me. Every other country in the world has signed up and ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. It doesn’t mean that it’s always worked everywhere. Compliance is still quite an issue, but it means that there’s a commitment to meeting certain minimum standards. There are minimum standards. These are basic rights that everyone has agreed to.

One of them is about the right of contact with the parent. The right not to be discriminated against on the basis of your parents’ situation. It’s the right to have the child’s interests taken into account as a key consideration in any decision that affects them. That includes imprisonment of a parent, for example. There’s so much in there. The Council of Europe has released a set of recommendations about children with a parent in prison. That translates the UN Convention into what this means when children have a parent situation. It’s incredibly important and something that the US doesn’t seem to recognize for whatever reason.

The San Francisco Children’s Bill of Rights, that’s probably the closest and there was a lot of overlap between the UN Convention and the Children’s Bill of Rights, but it’s how to make that a bit more deeply embedded, I suppose, to recognize in both state and federal legislation. That would be amazing. It’s interesting because with things like international standards, certainly when I was living in the US, it was difficult to find out what was happening in other countries. That was one of the reasons that I came over here. I was originally supposed to come over only for a year.

It was so eye-opening to see how other people address the same types of problems. To see your own country from the outside is enlightening. One of the things that I like looking at, you mentioned in my biography about the interesting comparative criminology. It’s learning how other countries do things, learning from positive practice but also learning poor practice. What is it the other people are doing that you know not to do? What is it that you can learn?

A lot of people are facing the same types of challenges in terms of how do you interpret family contact. How do you identify who these families are in order to provide support? How do you deal with these types? COVID was a classic example of learning about how other countries responded to that. It’s knowing that you’re not doing this alone is hugely important. There are so many benefits to these international collaborations and international networks, international standards like the UN Convention and the Council of Europe Recommendations.

It also brings in a level of accountability so that if you’re having a conversation with the legislature or something, you can say, “This is what we’re supposed to be doing. This is what’s been agreed.” It’s also the power of collective voice. It’s not just about you’re the one saying this, but all these other people are saying this as well. I know that certainly, the UN responds much more quickly when it’s a group of people or a group of member states saying the same thing as opposed to a lone voice. I am a strong believer in these international networks and alliances.

Learning what was going on and what could be so positive. That’s why I wanted to kick off season three of the show. Thank you so much for coming.

It’s my pleasure.

Any last words before we wrap up?

I’m looking forward to continuing the relationship. I enjoyed meeting you. I can remember it was a couple of conferences ago, maybe at the Texas Conference, another brilliant gathering of people who’ve had that shared experience. I look forward to seeing what happens next.

I interviewed you then, too. That’s when I first started. We got a little interview. Thank you again. I hope everybody that’s reading reaches out and learns more. Let us know if you have any questions. Together, we will make a change.

Thank you so much, Julia.

—

I want to tell you about the Prison: The Hidden Sentence book. There are so many things that you need to know when a loved one is taken into the prison system that nobody tells you. This book will provide valuable information to help you through the stages of the prison system with your loved one. I also share stories so you know that you’re not going through this alone. You can purchase your copy of Prison: The Hidden Sentence book on Amazon.

Important links

- Families Outside

- Prison Families Alliance

- Prison: The Hidden Sentence

- https://ChildrenOfPrisoners.eu/its-time-to-act-cm-rec20185/

- https://EDoc.coe.int/en/children-s-rights/7802-recommendation-cmrec20185-of-the-committee-of-ministers-to-member-states-concerning-children-with-imprisoned-parents.html

- https://www.UNICEF.org.uk/what-we-do/un-convention-child-rights/

About Prof. Nancy Loucks

Prof. Nancy Loucks OBE is the Chief Executive of Families Outside, a Scottish voluntary organisation that works on behalf of families affected by imprisonment. Prior to this she worked as an Independent Criminologist, receiving her MPhil and PhD from the Institute of Criminology at the University of Cambridge, and in 2012 was appointed as Visiting Professor at the University of Strathclyde’s Centre for Law, Crime and Justice.

Prof. Nancy Loucks OBE is the Chief Executive of Families Outside, a Scottish voluntary organisation that works on behalf of families affected by imprisonment. Prior to this she worked as an Independent Criminologist, receiving her MPhil and PhD from the Institute of Criminology at the University of Cambridge, and in 2012 was appointed as Visiting Professor at the University of Strathclyde’s Centre for Law, Crime and Justice.

Nancy was awarded an OBE in the 2016 New Year’s Honours List for services to Education and Human Rights. She co-chairs the Independent Review of the Response to Deaths in Prison in Scotland; is Secretary General to the Board of Children of Prisoners Europe; chairs the Board of the International Coalition for Children of Incarcerated Parents (INCCIP); and is a member of the Global Prisoners’ Families Research Group at the Centre for Criminology, Faculty of Law, University of Oxford.

Leave a Reply