In this interview, Juan Ortega talks about how he created his believable art while incarcerated and shares how much it helped him. He shares about his relationship with his family and how important communication is. Listen to or read his insightful words:

Transcript: (edited for readability):

“There’s no eraser anywhere that can erase the past, but there is a pencil that you can write your future with.”

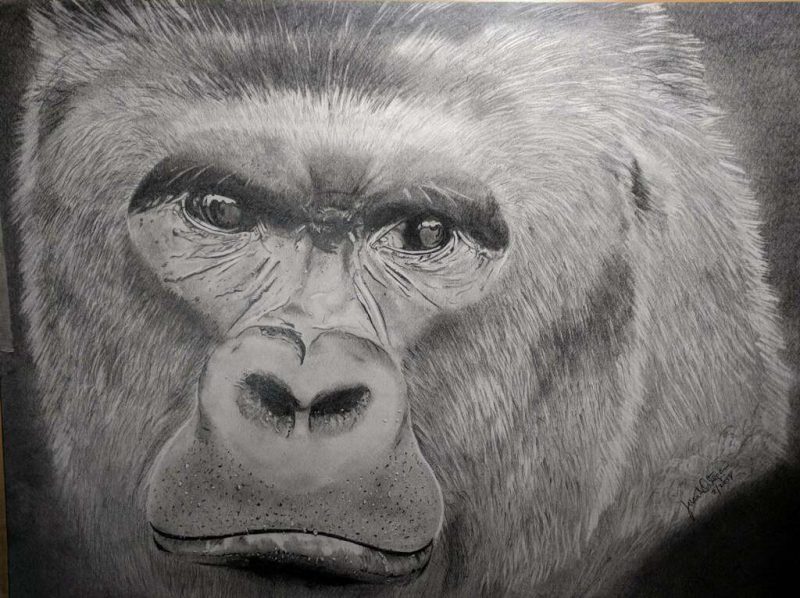

Julia: Hi Juan. Thanks for joining me here today. I’ve seen your drawings and I just think they’re amazing and you were telling me that that’s something that is self-taught. Could you tell me how you got started with drawing?

Juan: Because of my incarceration, the only way that I was able to communicate with my daughter, who was 13 at the time, was through drawings. She liked my drawings so it forced me to do as many pictures as I could so that I could mail them to her. And as I did that, I started asking for books about drawings and seeing other individuals that were talented and I would get pointers from them. Then I just progressed through that. Eventually I just started doing my own things, looking at pictures from magazines or pictures from my own family and started drawing them. That’s how I developed my skill, just by picking up a pen, a pencil, and put them on paper all the time.

Julia: What kind of pictures did you send her?

Juan: She is an avid Yankee fan, so I drew a picture of her favorite player at the time. She loves dogs, so I drew different kinds of breeds and everything that I could find in magazines. I also drew birds. And then I started challenging myself in what I drew. I’d try to find as much detail as I could in every picture. And also, the level of difficulty, either in motion or like the bear that I showed you that that’s running in water, drawing the little droplets of water as he was running and things like that. So, I started challenging myself and since I had the time to do it, I just got better and better at it, and I loved that. That’s something that gave me peace and kept me sane in a pretty insane place.

Julia: Did anybody ever asked you to draw for them?

Juan: Yes, I’ve done quite a few portraits for people that were inside. A lot of people do it. You know, there is a somewhat of a currency system inside where you can use items from the canteen, such as soups and coffee and things like that. I did it for my own pleasure, for my skill. I didn’t charge anyone. I wanted to make sure that they understood that it was something that was selfless: I didn’t want to owe anyone anything and I didn’t want anyone to owe me anything. I guess that’s part of my military training and also, you know, I want it to be consistent. I didn’t want him to do something for free for someone and then charge somebody else. And so, I just decided, if anybody needed anything drawn, I would just do it.

Julia: Was it difficult while you were incarcerated to get pencils and, and different things to draw with?

Juan: At the beginning, yes. At the beginning you’re only allowed to have a number two pencil. It was a flexible pencil, which in essence it’s not really very good for drawing: it’s made out of rubber. It’s challenging but you make do. And once again, that’s something that gave me a lot of peace, you know, and made me focus on my own life and reflect on the things that I have done. It kept me from really losing my mind in a place that is so isolated from society. Eventually I was able to join an art class. Only certain individuals were allowed to take those classes. The classes were run by a volunteer that came into the prison and was graceful enough to teach us.

I was able to learn at that point how to use the different weight pencils. The ones that have softer graphite. So, I just started seeing different depths in the drawings and that’s how I did it. I mean, at the beginning I learned a few tricks with just a number two pencil: if you want to make it a little darker you dip it in a little bit into mayonnaise and it actually makes it darker. Yeah. You started learning, you know, different things with what you have available to you. It was interesting and I learned a lot of things just by watching and reading books and things like that.

Julia: Any other tricks that you can share?

Juan: For example, when you do drawings and you need to shape the picture, instead of drawing on the paper you rub the lead on the floor. Then you take a little piece of toilet paper and you just dip it in the graphite, and you can do the shadowing into the pictures. Like I said, it’s difficult to do with a flexible pencil. I do understand the reason and the safety issues for people that are incarcerated to have those kinds of things, and it made me more creative in a sense to try to get things to look more realistic.

Julia: I’ve never seen a flexible pencil.

Juan: Oh yeah, you can buy them in the store now. The pencil is difficult to use because it’s flexible, so you really have no dexterity with it. It was a challenge then and I think it made me a better artist.

Julia: Now that you’ve been out, what kind of pencils do you use?

Juan: I just bought a basic set of pencils. Basically, they are graded into different weights. They go from H, which are the hard pencils, which go from one to about five. There’s HB, which is basically your normal number two pencil. And then you go into the B’s, which are the softer leads and they go from about one through about eight. The softer the pencil, the more graphite you’re applying to the paper, which makes it a lot darker, a lot of deeper color. So, it’s definitely a lot easier and more interesting, allowing for more detail to get more things from a picture with a variety of pencils that I have now. I enjoy it.

Julia: I’m just amazed by what artists can do with pencils and make these textures that are so life-like.

Juan: I’ve seen work from a lot of young people that are just absolutely amazing and obviously young men and women that are trained and have a schooling in it. And those are the things that I try to learn from. But the amount of detail that you’re getting in the picture is not as difficult as it is to capture what the picture is saying.

That’s what motivates me to draw the eyes, because anybody can draw a face. But capturing what the emotional, the person in the picture is, is definitely more important to me. And a lot of people have told me that’s my niche in the art that I’m doing, that the emotion that they see from the person is actually reflected in the drawings that I do. So I, I take that as a very big compliment, you know, because that’s what I shoot for.

Julia: What kind of pictures are you doing now?

Juan: Well, I’ve done a couple of portraits for people that have asked me. Just for gifts and things like that. But I also enjoy drawing animals and I venture into going into bigger papers in the sizes because when I was learning I was drawing on 8×10 size paper. Drawing in bigger scales is a little more challenging because then you have to really be careful about the details. The bigger the picture, the more details that you have to put in. So it is, it’s definitely a challenge and I love it.

Julia: Do you still draw pictures for your daughter or is she grown up now?

Juan: Actually, I’ve done only a couple, you know, she’s already in school. She’s an adult now. I haven’t drawn for her for a long time, but one of my favorite things that I actually did while I was in prison is, and I did it with an ink pen, I drew the Yankees emblem on a handkerchief and to this day she hangs that in her dorm room. So, that’s awesome. You know, it’s something that she appreciates. I would love to draw all kinds of things for her, but I don’t want to overwhelm her with my pictures when she’s got posters of her favorite sports people in her dorm himself, but that one handkerchief always hangs in her in a dorm room side. I appreciate that from her.

Julia: That’s really special. Where did you get the handkerchief and paper?

Juan: The handkerchief, they used to sell in the canteen. You’re allowed to have certain amount of paper in your personal locker, but it has to be a basic paper. You cannot have any special type of paper or anything larger than, 8×10, depending on the facility that you’re in. My family was very supportive and sent me paper. If I recall correctly, it was something like 10 or 15 sheets of paper that were allowed in. That’s it. That’s all you can have. As I ran out, I would let my family know that I’m out of paper and ask them to send me more paper. And that’s the way that I used to do it. I’ve seen pictures from other inmates on envelopes and, and other things. Not everybody has the family support.

Julia: It’s wonderful that you had the support and I think that’s why when you came out that you’re doing so well because you have family support. It’s just amazing that any piece of paper that people can find that they’re drawing on it.

Juan: Yeah, there’s incredible talent in prison. People make three-dimensional birthday cards with just paper and folding it. It’s just amazing. I mean, a lot of people don’t realize that when you have limited resources, how inventive and creative you can get. And there were a lot of people that did that and a lot of people.

Julia: Did you do that for your family?

Juan: No, I didn’t have that talent. The individuals that did this, I mean pop-up pictures and things like that for in their birthday cards and Christmas cards and things; it was amazing. I was always intrigued by that. But no, I stuck to a drawing and using a pencil,

Julia: That reminded me that I would get cards from my brother and he wasn’t an artist either. We didn’t get that artist gene and he probably asked other people who had those talents. And I still have the cards where people drew birthday greetings, or they would take a part of a card and somehow draw on the face of it. It was just interesting. But yeah, I still have that.

Now that you’re out, aside from your drawing, what else is keeping you busy?

Juan: I’m a veteran and I’m fortunate enough to have, benefits through the VA and I’m going to school. I was able to finish an Associate’s degree in engineering technology and enrolling in school for web design. I think that’s going to be interesting because it’s creative. I like to keep that creative and I think that’s going to be very beneficial for me. I’ve never done anything like that. I’m not really very good at computers anyway, but I think that’s something that’s going to open up maybe a couple of doors for me,

Julia: One of the things we were talking about, too, is that when somebody comes out of prison, even with the support of their family, that it can be really difficult to find work. So going through these programs and working on websites and things like that, I think will give you a better opportunity to work on your own.

Juan: Well, you know, one of the things that I found on my own as far as the people that I met while I was incarcerated is there’s this really, actually a lot of people that are educated in prison. Not just because they were educated from the outside in and went to prison, but also because they have educated themselves in prison.

When you have a record, society just looks at you as someone that committed a crime. That’s unfortunate because the amount of talent, the amount of intelligence, amount of academic knowledge that is within the prisons is outstanding. I know people that were very versed in theology, people that have studied engineering inside the walls, people that have a very eloquent and very knowledgeable of an array of different things that they can utilize out here if only given a chance. You can’t change society overnight. I’m very grateful for what you’re doing and the support that you’ve giving the families and the people that are incarcerated now. So, I applaud you for that.

Julia: Thank you. And that was a really good segue because the next thing that I was going to talk about is the prison family. That’s something that we’re focusing on now. Not just everybody on the outside, but the prison family consists of those on the outside and the person that’s incarcerated and hopefully coming home someday. You are part of a family, you stayed in touch with your family, they supported you when you were incarcerated and then when you came out, they were there. Maybe you can talk about the importance of having your family support you while you’re incarcerated and then how they supported you when you came out.

Juan: My biggest support was actually my sister, her husband, my son, and my mother. Unfortunately, my wife was very angry with me for a very long time, which is understandable because I’m the one that got incarcerated. And because of that we lost everything. We lost our house, we lost cars, things that made our life easier. She had to take care of everything on her own because I was incarcerated. My daughter was very young, and she was very confused, so she didn’t know how to communicate with me. So that support that I got from my sister and my mother and my son. When I left prison I had a place to stay, which was wonderful. I stayed by my mom’s for a period of time and they provided anything I needed.

It’s definitely a blessing to have someone that is caring enough to look at you as a person. So, you know, when you go beyond that point, you become very self-aware of how people really care about you and you want to do the best that you can for your life to improve your life so that their help is not in vain so that they know that you’re doing your best, not just for yourself, but also for them. So yeah, it’s really true that statement, families are doing time with their loved one. So yeah, that support system is very important. You’re incarcerated and they’re now incarcerated. That’s very true. Like I said, me personally, I disrupted our lives completely.

I went to prison and my wife had to do everything on her own. She had no place to stay because we lost the house. She had to get her own apartment. I lost my job because of my crime and then went into prison. So that income is no longer there. Even though my wife worked, losing one entire income is debilitating. The house that we had, she couldn’t pay the mortgage anymore, so she had to sell the house. There were the cars that we had, one of them had to be turned back into the dealership because the finance company would not help with the financing of that vehicle.

Even though she turned in the car she still had to pay the balance. And then of course she had to take care of our children. I wasn’t there, so she had to do everything for my son and my daughter, which we’re still young and still in high school in junior high school at the time. These are difficult ages to deal with and she had no support because I was incarcerated. It made it very difficult for her. So yeah, that’s financially, it’s definitely detrimental when someone gets incarcerated.

Julia: What about how your family was treated after you were incarcerated? Did they talk about it? Did the neighbors know? Did the community?

Juan: Yes. My wife told me that one of our neighbors just left a note in the mailbox saying that she was very concerned and she felt bad, but she wanted to respect her privacy. The note read that if she ever needed anything that she will be there for her.

And that was wonderful. But that was just one neighbor. I don’t know what everyone else thought. My wife had to sell the house and move into a different neighborhood. And that I think was silver living and saver her from people whispering or whatever they do. So, she rebuilt her life and my daughter had to transfer to a different school. My son was already in college. When she did that, it was difficult. People are going to have their opinions. I mean, my own family have their opinions. I’m right now estranged from my brothers. They won’t speak to me because I was incarcerated. They don’t see me anymore as someone that was their brother. They’d just be assuming someone, someone that’s imprisoned, someone with a record, I’m someone that they don’t want to deal with. But the way I see it is that’s really a weight that they’re going to have to carry. That’s not mine. That’s theirs. And when they ever want to speak to me again, I’ll welcome them with open arms. They are my brothers. But until then, I leave them alone. I’m not going to force myself into their lives. That’s not my job.

Julia: That’s why I think it’s so important to have these conversations so people can understand and can talk about it. That when people become more aware that they can go and talk to your wife and see what she needed; you know? So, I think this is just really important and I appreciate it.

We’ve spoken about your artwork, your family, and let’s travel back in time because you were in the military. You are very decorated person. You were telling me some of the things that you accomplished there. And one of the things that people don’t talk about as much as we probably should is PTSD. So, if you could talk a little bit about coming out of the military and how that affected you.

Juan: Well, I think that was the beginning of my down spiral when I first came back from Iraq in 2006. I was there for 18 months for training. I got deployed in 2004, so that experience alone, no matter how strong minded you are is going to have some kind of effect on you and PTSD, which I had no knowledge of until I was diagnosed with it, can be very debilitating. The things that transpire there sit in the back of your head. Then all of a sudden you come home, and things just started coming to the front of your mind and won’t leave you alone. It’s unfortunately a very serious, and yet not visible, disability and is something that is affecting our military presently.

I know that the statistics are 22 military members commit suicide daily. And that’s a sad thing. I hate to admit that I almost got to that point, but you know, there is a lot of help out there. People need to be more aware that this problem exists. That is not a weakness. That it’s not changing your personality. It’s just something that immediately affects your mind and your state of being. You don’t even realize it yourself. I mean, it took me about almost three years before I actually realized that I had a problem. And in those three years, I was making my wife’s family, our children, my own family miserable. I didn’t even realize it. It’s a difficult thing to deal with, but it’s definitely something that is treatable.

There’s a lot of help out there and I just hope that people become more aware of it. It’s not so openly spoken about because a lot of people feel that is a sign of weakness. And I’m talking about the people that suffer from it. It’s not a weakness. It’s something that the normal human mind is not equipped to deal with when you go into a battle zone.

Julia: Looking back, can you pick out some signs that if you had known then what you know now that you could have gotten help sooner?

Juan: Well, now that I learned, because I didn’t see it on myself when I first returned from Iraq. You become very withdrawn. You become self-centered to an extent. Things that brought you joy in the past became a nuisance.

The ability to connect with other people becomes difficult. In essence, you become numb. You’re not capable of feeling love or compassion or even anger. You become this numb, zombie-like existence and in your mind you think you’re okay, that everything’s fine, but it’s not. Once you see someone that’s becoming very detached and into their own little world, that’s one of the major signs. I’m not a doctor or anything, but just from my own experience. I just know that what I went through took me a long time to realize that I was suffering from post-traumatic stress (PTSD). I didn’t have any clue prior to that. I was just thinking that it was bad memories that I could get over. That I could get over it soon. I kept convincing myself that that’s the case, but it’s not.

Julia: Was it during that time that you committed your crime?

Juan: Yes, and I’m not using that as an excuse by any means. I know I was not in my right state of mind. I know that is something that I made a decision, you know, a clear decision. I don’t like using my condition of PTSD as a crutch. That is something that I have to deal with. But that’s something that is definitely relative with everything that happened when I was incarcerated. I had to take responsibility for what I had done. So, I did my time and now I’m here

Julia: I must say that a lot of people that I’ve spoken to, including my brother say that they’re not guilty. Some people are and some people aren’t. You’ve always owned what you’ve done. You’ve paid your time and now you’re out.

Juan: I owe that to my father the way he raised me. But more importantly, I thought about the impact on my children. And what I mean by that is I wanted them to know, even though I committed a crime, that you have to be responsible for what you do. The more excuses you make, the more, lack of peace you’re going to have. I’m in peace with myself. I know that what I did was wrong and all I can do is look towards the future. There’s no eraser anywhere that can erase the past, but there is a pencil that you can write your future with. I don’t like to show my children that I make excuses. I like to be truthful. I like to be honest. I like to know them as they are and I want them to know me, as their father, as I am.

Without honesty, I think the communication is crucial and it’s been a salvation for me. You know, being honest with my children and teaching them to be honest and to be caring and to be truthful is important to me. Even though I was incarcerated, I think they know that even that experience taught them something, you know, they told them what not to do. That’s what I want them to know and I want them to be better people. Hopefully when they are old enough and they have children, they’ll do the same

Julia: Well said. And that’s something that I admire about you.

Juan: Thank you. It takes a tremendous amount of effort to cover up lies, you know, and it’s just a lot easier to be truthful. Truth hurts sometimes, but in the end, truth affects the people around you and affects you. So as long as you’re being honest, as long as you’re being truthful, that pain, that truth may cause is easily eradicated because there were no lies behind that. There’s no nothing to too muddy the actual truth. When you lie or when you try to make excuses for anything, you have to continually do it, you know, to make those lies half-truths. So, you have to continually build on lies and lies. And that’s actually a lot more work and a lot more pressure and it’s unnecessary. Truth is a lot easier.

Julia: From everything we’ve spoken about, it seems like your family, your strength, your beliefs have gotten you through this and I really appreciate you sharing. Anything you want to say to or about your family support, or other people that are involved in this situation?

Juan: Well, the one thing that I can definitely say is that being incarcerated is a difficult experience. However, I know that the families suffer a lot more because once you are incarcerated you fall into a routine. You’re being told what to do, when to eat, when to go places, when to take a break, when to go out on recreation, and when to sleep. So, it becomes a routine. Whereas the people that are on the outside, the families, are constantly worrying about you and constantly thinking what’s going on and worrying about your safety and your well being. The only thing that I can say is just hang on to the faith of the fact that nobody in this world is really in control. I believe in the higher power and God has been very good to me. I’ve been blessed with my health and my family and my friends and with opportunities like this one: to be able to bring some sort of clarity to what my experience has been inside the walls. I hope that if anything, some of this conversation is at least a comfort to some of the families out there that still have people who are incarcerated.

Julia: Thank you and I did have one last question that I’ve been meaning to ask them. I think we did have this conversation once and it’s really just my wondering what the difference is between coming out of the military after being in a war zone, which is very regimented when you’re in the military and coming out of prison, which is also very regiment regimented. What is the difference? You’re one of the few people, I think they can talk about the difference between the two.

Juan: There’s a huge difference. The difference is actually in your mind and in your soul. When you are in a war zone, you are doing a job. It’s difficult to put in such simple terms, but that’s basically what it is. You’re doing the job, you’re working for the government at the time, and this is what you’ve been trained for. So, coming back from a war is more of a, okay, I just finished my job and onto the next thing. Whereas coming out of prison, you did not plan to go to prison. You did not want to go to prison. It was the circumstances of your decisions that put you in prison and now you have to deal with searching for a way of forgiving yourself for doing that, making yourself a better person from doing that. And then the fear of walking out of those Gates and saying, okay, now what? I have a record. Society is going to look at me differently now. So, what do I do next? It’s definitely a big difference between coming back from a war zone and being released from prison with those uncertainties. Whereas when you come back from a war, even though it’s a difficult thing, you’ll still have your life and you still have a career and you still have something that is tangible for your future. Whereas when you come out of prison you have to start pretty much from scratch.

Julia: That was really interesting. I just always wondered what the difference is because they’re both regimented. I really appreciate you sharing and clarifying that.

It’s just always a pleasure talking to you. I know we’ve had lots of conversations and I think we touched on pretty much everything we’ve wanted to.

Juan: We have. I really want to thank you for asking me to do this. It’s not just something that’s important for people to be listening to my experiences, but it’s also a healing process for me. Even though things are in the past and you can’t do nothing about them, you still have to learn from your experiences and things that sometimes haunt you. You have to learn how to move forward and forgive yourself for the things that you’ve done. Thank you so much for this opportunity.

Julia: Thank you and we’ll talk more. I think that you have so much to give and share and if people want to see the work that you’ve done, they can go to your believable art website: https://believableart.com

For VA Help on PTSD click here:

VA Help Line.

- Dial 1-800-273-8255 and Press 1 to talk to someone.

- Send a text message to 838255 to connect with a VA responder.

- Start a confidential online chat session at VeteransCrisisLine.net/Chat.

- Take a self-check quiz at VeteransCrisisLine.net/Quiz to learn whether stress and depression might be affecting you.

- Find a VA facility near you.

- Visit MilitaryCrisisLine.net if you are an active duty Service member, Guardsman, or Reservist.

- Connect through chat, text, or TTY if you are deaf or hard of hearing.

Globaltel says

Wow, his art is truly amazing! Arguably one of the best style of art there is. But his is surely one of a kind though. Being incarcerated doesn’t stop your passion and your being as an artist. This proves that talent doesn’t have any limits, even if you’ve committed crimes before and now you’re being incarcerated, it doesn’t disappear or is stolen form you.