The criminal justice system has implemented efficient regulations in throwing wrongdoers to jail. However, it fails miserably in providing recovery support once they get out. David Rothenberg was able to change this poor aspect of the New York’s correctional system all thanks to one trip to prison in 1966. He joins Julia Lazareck to share how producing an off-Broadway play about incarceration inspired him to start Fortune Society. David shares how he and his team provide a safe place for formerly incarcerated individuals to heal from trauma, take off figurative jackets of protection, and transform them into powerful people who can contribute to society. Come along on a journey through time that led to changes in legislation in New York.

Listen to the podcast here

David Rothenberg’s Legacy – How One Trip To A Prison Created Changes In The Criminal Justice System In New York

Thank you for inviting me.

It is a Shakespearean sonnet. The title of the play was from Shakespeare’s, “When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes, I all alone beweep my outcast state.” I was working in the theater. I was a publicist. I knew nothing about prison other than old movies. That is my frame of reference, like most Americans. It was Cagney pictures. They were either escaping or rioting. I worked in the theater, mostly doing publicity and doing it well. I read this play, Fortune and Men’s Eyes, which was sent to me by a critic. I read it one night. I was devastated when I read it. It was by a man named John Herbert. It’s about a kid who goes into jail and is raped on his first night in prison.

It was good theater, but it also rang with the truth that was unmistakable. I was shocked and angry at myself because I considered myself politically and socially active, sophisticated, and knowledgeable, and this was a world I didn’t know, but I knew a good play when I read it. I wrote to John Herbert. I said, “I’d love to see this play get on.” I had never produced at that time. I showed it to a couple of friends who were successful producers. They said, “Nobody’s going to want to see a play about a kid going into jail.” I said, “I’m going to get it on.” This was 1966. It’s a lifetime ago. I raised the money and it was off-Broadway.

It wasn’t Broadway. This play could have never opened on Broadway back then. It was too startling. It had to find a small theater and its audience. We cast the play and the actors went into rehearsal. They came to me one day and said, “We want to visit a jail,” because as actors, they wanted to authenticate the movement and whatnot. They were playing young men. It was a juvenile facility. It was arranged for us to go to the adolescent unit on Rikers Island in New York City. I went with them. It was my first visit to jail. It was December 1966. We spent a full day there. We spent a day watching them being watched around. We spent 1 hour or 2 in the dormitories.

I saw teenage boys. Almost all of them were sitting on their beds looking out. They put us in each cell for one hour so we could get the feeling of it. They were nice to us. I’m looking at these boys. They were big kids, but they were boys. They were 16, 17, and 18. I remember the sense of eyes. I could feel the eyes looking. I thought, “This is what my initial instinct was in jail as a person who had no experience with it.”I said at the meeting with you when I met you that my greatest strength was the fact that I didn’t know, but I kept asking questions.

My reaction to the boys in that jail was, “Whatever they did that got them there, how could they be any better as a result of this experience and what would society be inheriting when they came back out?” I was interviewed by a theater newspaper backstage and they wanted to know all the show business aspects of what we were doing. I said, “This is an exercise in institutional futility.” I say that because I have been in jails and prisons hundreds around the country and in other countries. I’ve never changed that initial reaction. The worst is what I’ve seen in the States that it doesn’t work.

The system is counterproductive to the needs of the greater society. There weren’t many articles. Back in the ’60s, there wasn’t that much to read, but I read Bill Sands’ book and a couple of other things. Every now and then, there’d be an article in the newspapers. I started reading things and learning about what was happening in jails and prisons. When the play opened to wildly diverse reviews, some of the critics said it was one of the most important plays of the year, and others were so shocked by it that they said it shouldn’t be allowed to be seen.

About three weeks after the play opened, I got a call from a professor who was bringing his students to a performance, “Could they stay afterward for a dialogue?” That was right up my alley. I invited the whole audience. We put a note in the program. Everybody wants to stay. Almost the whole audience stayed because, by the time the play was over, the audience was gasping and needed to have some feedback. They wanted a dialogue. Myself and two of the actors came out on the stage and we invited comments. They were laudatory and wonderful.

One man said, “This play is an exaggeration. Those characters are stereotypes and exaggerated.” From the back of the house, a man stood up and said, “None of my twenty years in joints like this count for anything. You, people, couldn’t watch what we do to each other and what happens.” I was like, “Johnny Olson, come on down.”

A man named Pat McGarry came down and mesmerized the audience for the next hour talking about state prison, Florida chain gang, and San Quentin. He had been there. Afterward, we went across the street for coffee. We talked for hours and I said, “This is important. You have to come back.” He said, “Everybody knows about that.” I said, “Nobody knows about it. You may be in a world where everybody knows about it. I’m mainstream America. I’m as square as you can be. This is news to me.”

He said, “You got to get somebody that did Black time. I did White time.” I said, “What do you mean? He said, “Most of the prisons in the ’60s, New York State, there’s Black time and White time. We don’t mix. It’s two different times.” I said, “I don’t know. You’re the only person I ever met that did time other than the playwright.” He said, “I work in a tailor shop. I have a customer. We don’t talk about it, but we read each other.” He came back the following week with a man named Clarence Cooper who was African-American and who did time in Milan, Michigan at a Fed Joint.

They were totally opposite. Pat was flamboyant and outspoken. Clarence was intense and intellectual. It was almost like you were casting it for a movie. It could never get better. They loved doing it because it was almost therapy for them because they had never talked about it. Clarence was in a relationship. The woman came to those sessions. She didn’t know any of the things that he had gone through. It was very therapeutic.

Because I was a good publicity person, I called an Editor in the New York Times and said, “This is a story.” He sent a reporter down. The headline was, “The drama continues after the curtain falls.” It said that every Tuesday night we were having these dialogues at the theater. The following Tuesday night when we started, I suddenly realized that in the audience was a whole different population. There were at least a dozen guys. I keep saying men because it was a couple of years before women came forward for lots of obvious reasons. These guys all had something to say.

All of us went across the street to the coffee place afterward and had coffee. When I discovered that somebody had given them the article, they either read it or somebody passed it on to them, almost every one of them was an AA and they had a place to go to deal with that. They all said that if they stayed sober, they stayed out of trouble, but what came out of that and future Tuesday nights is that their rage about their prison experience had not been expressed. They had deeply felt anger about what the system had done to them and was continuing to do to them because of jobs and housing. One of the guys’ wives signed the lease. It was demeaning to him.

Another man said, “My grandmother thinks I was in North Carolina working on a farm for three years.” He lied to her. There were lies to people you loved. There were jobs you couldn’t get. One guy was a gypsy taxi driver with a fake license, all endangering their freedom, but surviving. I was discovering that not only was the system inside horrendous, the punishment continued when they were out. I started getting phone calls from people in the audience. This was in the late ’60s when there was a lot of social activism and protesting but this was an unheard group.

A lot of these guys were joining us on the stage on Tuesday nights. I started getting calls from teachers and ministers, “Could you come and speak to our group?” I was suddenly on the circuit going to college classes, high school classes, rotary clubs, Presbyterian Church, and suppers. We did that for about six months. One night at the theater, I said, “We have the nucleus of an organization. What we could do is what has to be done. Educate the people because if they knew what was going on, we could change the system.” I had no vision beyond that. I was naïve.

We decided to take the play’s title, Fortune and Men’s Eyes, and call it The Fortune Society. Sixteen people gave me $2 and we opened a bank account for $32 at Chemical Bank. We outlasted Chemical Bank because Chase bought them out. In my little theater office on 46th Street, I was still working in the theater. I was doing publicity on Broadway shows like Hair. I was representing plays by Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee.

The criminal justice system doesn't work. It is counterproductive to the needs of the greater society. Share on XMy theater office became headquarters for The Fortune Society. We said we were going to keep in touch with people by mimeographing and newspaper. Anybody under 50 doesn’t know what a mimeograph machine is. It was the prequel to xeroxing. There was no email. This is significant because it was 3 or 4 pieces of paper saying what we were doing.

Men in prison started hearing about it and asking for copies. This was significant because the warden at Attica banded saying it was revolutionary. There was nothing in it except us saying where we were going because they said it was revolutionary. We started getting all sorts of letters from men at Attica. This is 1969 and 1970. A law student named Steve Sikowski who volunteered with us, a Columbia law student, got a law firm and they challenged the banning of our newspaper.

Fortune versus McGuinness has become and still is a landmark censorship issue, which says, “When you lock somebody up, you don’t have the right to deny them what they can read.” I say that because there are still prisons that ban literature and they’re doing it against the law. The men and women incarcerated don’t know the law. As publicity people, we started doing radio programs and guys were using fake names, so they wouldn’t be caught.

There was a national syndicate program called The David Susskind Show. The nearest thing to it for people nowadays was Oprah. Oprah had that kind of a program. It was on Sunday nights in New York but played around the country. He had always had interesting topics, 6 recovering addicts, 6 gamblers, 6 lesbians, and all sorts of things. We could never get formally incarcerated people to talk about their imprisonment because of the fear of what would happen to them, jobs lost, and whatnot, but some of our guys said they would go on. Susskind ran the program on a Sunday night.

At the end of it, he said, “These men are all part of a new organization, The Fortune Society, 1545 Broadway,” which is my theater address office. The next day when I arrived at my office, which is on the 6th floor of a 6-floor building in Times Square, Manhattan, the stairwell from top to bottom was filled with guys who had seen the show, thinking they were coming to this big thriving organization because they saw these four terrific guys expounding on what’s wrong with the system. The guys came in, “I need a job. I need housing.” There was me sitting there with my theater posters.

I didn’t know what to do with them. One after the other, I was telling them, “We don’t have jobs. I don’t have housing. We don’t have a drug program.” Kenny Jackson came over with me and said, “You know what you’re doing, do you?” I said, “Help.” He said, “Move over. I’m a drunk.” We talked to each other. He became the first counselor right there. Later in the day, a man named Mel Rivers came in African-American from Bed-Stuy. I said, “We don’t have jobs.” He said, “I’m not looking for a job. I just want to know what you guys are up to.”

He and Kenny hit it off. Melvin was working as a gypsy taxi driver. Kenny was working as a trucker with a fake license. In retrospect, I realized that they had great leadership ability and they both knew this was something they wanted to do. We had a nucleus. This was about six months after Fortune began. We started going around places and talking. In that Susskind program, we got brought out to Chicago and met the manager. Attica jumped off in ’71. Do you remember? Were you around during the Attica?

The men inside took over the yard and protest about the conditions. They didn’t trust the city or the state and in negotiations, they asked for outside observers to come in. They made a list of people whom they and the state would accept. I got a call from assemblyman, Arthur, saying, “The inmates want you to come to Attica.” It was as a result of our fight for censorship to get a little nasally newspaper into Attica.

They thought we were this thriving organization. I said, “I’ll come up, but I didn’t have much experience with prison rights. I won’t come alone. I have Kenny Jackson and Mel Rivers come with me.” They said yes. The three of us did go into the yard. They takeover of the yard and subsequently the state, going in, killing 33 men and 9 hostages.

It was the news story around the world, certainly around the country. It was a lead story in all the television news and the newspapers. In New York City, we were the only game in town for the media. Every day, for weeks afterward, we had a lot of guys who had been in Attica. They wanted our perspective. We grew incredibly as a result of Attica. Men started coming to us. I had to make a choice about two careers, whether I am going to stay in the theater or is this what I wanted to do?

Those of you who have been involved with nonprofit organizations may find this interesting. I got a call from a man. He was a lawyer. He said, “I have a client anonymous who wants to make a $5,000 grant to your organization. What is your 501(c)(3)?” I said, “What does that mean?” He said, “Your nonprofit status.” I said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” He said, “You are grassroots. Don’t you? You need a nonprofit status so you can raise money.” I said, “Now what do I do?” He said, “I’ll help you.” Through the Attorney General’s office in New York, he got us the nonprofit status. Kenny, Melvin, and I went on salary at $100 a week in 1971. For a long time, I worked both in the theater and on my job.

We started growing from that. One of the interesting things we were in this building on 46th Street on Broadway, which was almost all theater people. It became the safest building in Times Square at a time when there was a lot of trouble. The people in the building were always, “Do you have a guy that we could get for a day’s work to do some painting? Do you have a guy that we unloading some stuff?”

The word was out around Time Squares, “Don’t mess with that building because a lot of guys came for coffee.” We started collecting clothes but then we got so big. We wanted to move and we had trouble finding a place that would take us because of who we were and the place where we were started petitioning to keep us. They made space for us to move out of my 1 room into 3 rooms so that they could keep us in the building.

That was only for another year because by then, we were bursting at our seams and we finally found an area which at that time was reconstructing. We got in there, but it’s interesting that every time we wanted to move because we were getting bigger, the new places didn’t want us, and the old place where we were said we were such good neighbors and made the building so safe that they wanted to keep us. It’s an interesting paradox about, “Not in my backyard,” thing. We’re going through it with one of our residents. Some people in the North Bronx, “We don’t want them there,” yet we have a residence. I’ll get to all of the people we’re part of the community.

Fortune grew from that beyond my wildest dreams. People say, “What was your vision?” “To get through the day,” was my vision. People come in with problems. I was a middle-class kid working in the theater. I heard life stories almost every day. Somebody came in and it was like a three-act play or a drama movie that you couldn’t believe. I never met people who were abandoned at birth, faced the death penalty, did 25 years, and then came out and, “How can I help?” The paradox was overwhelming. It committed me to something bigger than me. That’s what Fortune Society came into my life.

I was lucky. It was an arena at that time that was hungry for advocacy. That was my gift because my background was in public relations, publicity, and theater. I was able to be an advocate for a population that had no voice beforehand. As we grew and we started hiring people, it was the people coming into us that defined what our needs were. Counseling was obvious. This is how we started our education program.

One of our guys, Danny Keane was a very effective speaker talking about his experience. He said to me, “I don’t want to go to any more colleges. I feel ignorant in front of those people. They’re so smart.” I said, “Your story has to be heard. Standing there was one of our volunteers, a woman named Melanie Johnson. She said, “I’m a retired teacher. I’ll tutor you. You can build up your vocabulary and your grammar.” He said, “Okay.” Melanie came to me about three weeks later and said, “I now have five students who need another teacher volunteer.”

That’s how our education department was built because the people coming to us defined it. Housing became a need because people came in saying, “They are putting me in shelters and in single-room hotels.” I remember this guy, Prentice Williams, said, “If I have to go back there one night, I’d rather go back to prison. It’s filled with drugs. There’s violence all over. I want something else in my life. I won’t go back there.”

Institutionalized people need an atmosphere of trust. They must be able to express their feelings comfortably since those who come out of prison are not ready to open up. Share on XKenny, Melvin, I, and then other people offered the “halfway house” where the sofa’s in our living room. For a few years, that was it. I must have had 50 different men and a few women who stayed with me as time went by as all of us did. Some of our supporters started making it available. We knew housing was important. Eventually, “The Castle” became our model resident, The Fortune Academy, but that wasn’t until the year 2000 that it opened.

I stated Fortune for many years. It was growing big and I knew that it needed to go in another direction. My gift was that I did grassroots and advocacy. I said, “it needs somebody else.” JoAnne Page who had started as a volunteer when she was a Yale Law School and is the child of Holocaust survivors was almost the perfect person. Beyond that, the show is organized and bright. I went back and did some theater work, but became a full-time volunteer at Fortune. We talked a lot about housing. They found this abandoned building in Harlem at 140th and Riverside Drive. It had been a Catholic Girls’ School and then a crack house. She negotiated, got the building, and we converted it.

There are a lot of protests in the neighborhood. When we opened it, they picketed it. It’s a residence for 75 men and women formally incarcerated, all homeless. Every Thursday night, there’s a community meeting with the executive team meeting with the residents. I went to the first one. I’ve been going every Thursday for the last many years. It’s to shape a culture. It’s for institutionalized people. How do they break the cycle? You have to create an atmosphere of trust. That’s the toughest part, getting people to express their feelings and feeling comfortable enough because if they’ve come out of our jail and prison system in America, they’re not ready to share and to open up.

The Castle has been an incredible experiment. I’ve watched lives. Not everybody makes it. We have a 2nd and 3rd chance policy. JoAnne always said, “If you had been driven for 30 years, don’t think a 30-day program is going to get you a free pass. Relapse is part of recovery.” We have a lot of people who have been 2nd and 3rd times at The Castle, which is different from most. It’s not a halfway house, but I’ve gone around the country and looked at halfway houses. Most of which are run by parole or correction. They don’t have second chances. They don’t create an atmosphere that allows people to open up.

The best example was I was on the subway. The guy yelled, “David.” It was one of the residents downtown. I said, “Where you headed, Eddie?” he said, “I’m going home.” He was referring to going back to The Castle as home. That’s the first time I heard that. I said then to myself, “We’ve succeeded. At least with Eddie, he’s going home. He’s not going to the place.” We’ve been there many years. I said to one of the guys, “I haven’t seen Joey. He left The Castle a couple of years. How’s he doing?”

One of the other guys’ alumni, because a lot of the alumni come back to the Thursday meeting said, “He’s fine. I talk to him every morning on my cellphone.” I found out that there was a network of about 18 or 19 men and women who had all gotten to know each other in The Castle. Without any guidance from us, they stay in touch with each other every day saying, “Is everything okay? If you need anything, call me.” Sometimes they need things.

I found that fascinating, but that’s a result of creating a place that was supportive that gave them an opportunity. That’s exciting. The Castle was our first residence and then we had a backyard. We built a second building, which is for permanent residents. The Castle is temporary. You come in and you learn how to prepare to go back into society. You can make mistakes here with us.

I remember one guy said, “The guy down the hall, his music is too loud.” At the Thursday meeting, he came up and somebody said, “What are you going to do when you move into your own building if somebody’s making noise? It’s going to happen. Your situation is nothing unique. How do you deal with situations like that? Do we set up a tenants’ committee? Do you get together and talk about how to respect each other when people have all come from prison life?”

Fortune has the main office now in Long Island City, Queens. We have a staff of 400 people, which includes all the temporary residents and all our residents. We have two residents in the Bronx. One, the city came to us during the pandemic and said, “We’re letting people out of Rikers Island. We will give you a building if you will run it for us.” We invite political people and media people to come to see what we’re doing. They picked us to do what they didn’t think they were able to do. That’s what our second house is.

In the third house, the religious group was building a residence for seniors and a beautiful building. They said they wanted half of the residents to be from the Fortune Society and the other half to be church people. That’s one of our residences for people over 65 who have come out of prison. We’re taking a big hotel that has been abandoned on 96th Street and Broadway. JoAnne Page has done extraordinary work in creating housing options for formerly incarcerated men and women to give them a support system. 50% of the people coming out of institutions in New York are homeless. They want to know whether there’s a crime on the street.

They want to know whether there’s recidivism. A lot of people who have been maintained on Thorazine and other drugs in prison don’t have continuity when they come out. Those are all things that have to be talked about. Our advocacy continues to talk about things like that, but we also have to address the reality of it that we have people who are not on their meds, who can’t function off their meds, and get in trouble when they’re off their meds. It’s a lot.

The bottom line when we talk to people is when they say, “How do you reduce crime?” My answer is, “One person at a time. People who change their lives tell stories and have given me blanket permission to talk about him all the time.” He came to The Castle. He is in the late ’30s. He said at a meeting that at the age of ten, he was introduced to weed and wine. That’s how he dealt with his pain.

When he came to The Castle, he sat in on the Thursday night meeting, slouching, unshaven, looking like, “I would rather be anywhere else in the world.” I watched him each week. His posture got better. He started combing his hair and doing all the things. Years later, he said, “When you get into a lot of institutions, you sit around, you try and find out who’s serious and who’s not.” That’s what he was doing. After about 7 or 8 weeks, he said something in the meeting. I whisper to JoAnne, “He talks, too.” He became not only a talker but one of my closest friends and a marvelous man who became a counselor.

He still works for Fortune. I watched his kids grow up. His daughter and son are part of Fortune. He was taken away from his mother when he was six. The father wasn’t there. The mother was an alcoholic and they took away all the children. They scattered them around the state. That’s what they do with kids. There was no plan, no nothing. He said to me, “I had to learn how to trust. You all in this building made me feel like maybe.” I said, “We’re on trial all the time.” He said, “The trial’s over, but you were on trial and prove it.” There are lots of stories.

He is a remarkable man. He’s so smart. I think of what he could have been. I said, “How come you know so much?” He said he learned how to read early. He always had a book in his back pocket. His joke is that Mark Twain, Jack London, and Superman saved him from a lot of pain. He traveled in that world. He got lost in the world of books. He’s always telling me, “I read this good book. You got to get a hold of this.” He’s only one of many. It’s just that we’ve got close. I’m close to his wife, kids, and family.

You and I have both talked to people in different parts of the country. It’s rather scary because we move so much here in New York. I talk to somebody in Mexico, Wyoming, or North Carolina and found out they have a relative coming out and there’s nothing for them. The families are left with a burden that they are often not prepared to handle. That’s why groups like yours exist because they get feedback from other families.

Getting into relationships is not a free ticket. Learn how to maintain one before you go into it. Share on XWe’ve gone to different states. I’ve gone to Colorado, Charlotte, and North Carolina people call up and say, “Can we start a Fortune Society here?” I say, “We don’t want to be a national organization because everything is about the local, but you can come and visit us and we’ll come and visit you. You can emulate what we do, try, and create a program.” I tell them that if they want to get started, try to find a church that is committed to social justice so that they can have a place to meet.

It may not be a church, but that’s always a good starting point. Let AA groups and NA groups know that there is a program because you’ll find that many of the people have been incarcerated in groups like that. Have an understanding of group dynamics and their importance of it. They can be helpful and pragmatic things. You and I were talking about the meeting in which I met you where a woman thinks was she from Nevada where she said her father came out for a pass for three days.

They went to a big store and he ran out because it was so overwhelming, and he could make decisions. One of the women from Long Island said they remember Angel from Fortune telling that story. Angel at a Thursday night meeting at The Castle talked about how he went away when he was 18 and came out when he was 40. He said he couldn’t go into drug stores or supermarkets because it dazzled him. It scared him.

Because he was in an environment where he was comfortable enough to share that, two other guys in the room said, “Me, too.” They were going through the same thing. The three of them started shopping together. They called them three men in a shopping cart. They supported each other. They made themselves realize that a lot of this was people laughing at them, and nobody cared what they were doing.

I was excited by the fact that many years ago, Angel said that at a Fortune meeting. Somebody heard it and was at your meeting then, and then now somebody in Nevada, in New Mexico can try and can try and implement something like that. That’s what happened with the meeting I sat in with you. People were sharing information. It ain’t easy, but at The Castle, one of our guys said, “The answers in the room. You have to ask the question.” Now, we say the answer is in Zoom. Everybody who’s going through something thinks that they’ve invented this problem and they find out others through it.

I remember at a Thursday night meeting at The Castle, a new guy wanted to get his license. He talked about it. He was a truck driver before, and that gave him this trouble and that trouble. The guy across him said, “Here’s what to do.” The guy said, “What do you mean?” He said, “I faced it. Here’s what I did. Here’s what I got.”

The answer was in the room. Thankfully, the man talked about it because sometimes, especially guys who have done a lot of time and become institutionalized get frustrated that they think going back is easier than they throw a brick to go back in. They say, “The woman from New Mexico, her father said he wanted to get back in. It was easier for him.”

The room has to be created not judgmental and supportive. If it’s judgmental, “How could you have done that? How can you be so stupid?” These are things that adults say to kids all the time which closes them up. You have to create a room of trust and comfort, so people will express their frustrations. This is a New York City problem and there might be equivalents in other places. The subways are so crowded during rush hour.

People push. Inside, if you don’t push back, you’re perceived as a target. When you’re outside on parole and you push back, you can get violated. We talk about that. What do you do if you’re going to get pushed on the subway course? Guarantee, you’re going to get pushed. How are you going to handle it? By talking about it people are prepared for the fact.

Some guy says, “I arranged to go to work off rush hours,” which means he goes at 6:00 instead of 8:00. I said, “Eventually, you may get tired when you show up at 8:00.” We talk about it. The answers aren’t easy because you’re dealing with feelings and years. The wisest thing I ever heard is from a man named Larry White who came to The Castle. He had done about 25 years. He was wise because he had insight into what he was going through. He told the group, “To survive in prison, I had to put on jackets of protection one after the other. Living there year after year, these are not real jackets. These are figurative coats of protection.”

He said, “That’s how I got through it. I protected myself with all these coats. Now I’m out here. You all have to help me take them off.” That became a challenge. That was many years ago. His coats left and they’re all gone. The fact that he recognized that his metaphor was clear and precise, many other people identified with that. He was a standup guy who had done all this time and he’s putting it out there. It made it easier for other guys to say, “Me, too. I don’t know what to do.”

We talk about relationships. There was a terrific guy. He met a woman. He was at The Castle for six weeks and gone. He came back and he said, “She wants me to do this and that.” I said, “Relationship is not just about good s**.” I looked at the group and I said, “The golden f*** is not a relationship.” The whole room froze because I don’t swear and I’m older than all of them. If you use something like that and you know whom you’re talking to and they know you, it has an impact. I’ve had a lot of guys come back to me and say, “You were right about that.”

You move in with a woman. We have women who get into relationships with men. They recreate the worst relationships they had. It’s a phenomenon. Women who have bad men find other bad men and see if they can get one worse. I remember this guy said, “I thought it was great. I’m moving into our apartment. In a few weeks, she wanted to know if I was going to start paying half the rent.”

He said, “I’m going to school. I don’t have a job yet. She wanted to know about paying for half the food.” I said, “That’s what relationships are. It’s not a free ticket.” He said, “I got to come back to The Castle.” I said, “You got to come back to The Castle and learn how to have a relationship before you go into one. It’s not just good s**.” He said, “The golden f***.”

I tell the guys, “You don’t have exclusivity on this. You have it more intense because you’ve been locked up.” The women who come in have had many have had terrible experiences with men. My dear friend, Helen, said to me, “You’re the first men I’ve trusted in many years. I couldn’t talk to men.” She was so afraid. I didn’t ask for details. She’s a beautiful human being. She’s learning at 60 to have the life that she always deserved that she could and should have.

One of my wife’s friends, Sam Rivera, said, “They sent to me to prison, and that was my punishment. Nobody told them they had to punish me every day. That was not what the judge asked for. What I had to learn was why was I there.” Nobody ever asked him. People asked, “Why are you there?” His first answer was, “I got twelve cops who came and arrested me.”

There are no stupid questions. There are only unasked questions. Share on XThis was a therapist discussion. The therapist said, “No. Why were you there?” He said, “I was selling drugs on the street.” She said, “No. Why did a smart guy like you put yourself in a position where you could be killed or locked up when you had other options? What happened in your life that you made those choices?” The hard work begins is to figuring out why have you made those choices.

One of the guys that run our meetings many nights, different people do, but Stanley Richards is one of the wisest men. He says, “Look in the mirror tonight and ask that person, ‘Who are you and whom do you want to be?'” I remember one night, Irvin Hunt called. He came back the third time. He did well at the meetings. He charmed everybody and did everything right. He went out and got high when he got into his own apartment.

I had permission to share this. He talks about that in public. I’m not breaking confidence. When he came back a third time at the meeting on Thursday, he said, “Tell them all, David. What are you going to do? What do you want to be? What do you want to do?” Stanley said, “When you’re here in a meeting, you charm, abuse, and inspire us. What about you?”

Izy started to answer it. Stanley said, “You don’t have to answer any of us. The only person you have to answer is you. When you go back to your place tonight, look in the mirror and that’s when the hard work begins. What do you want? Do you have to go into an NA group? Do you have to go into therapy or is it a religious thing for you to find out? Why did you do this?” The traumas of the past and some of the stories we’ve heard are horrendous stories about childhood.

You think you’ve heard every story and then you’ll hear of a man who came to The Castle doing well. As I got to know him well, he told me, he witnessed his father killing his mother. He was about eight years old. I said, “What happened with you then?” He said, “All my relatives were in Puerto Rico. They just put me in a kid’s home.” I said, “Did you have any counseling? Any therapy?” None. The mother was dead. The father was in prison and he saw it. I’m like, “How could you become an addict? “He became a user of drugs because his life was beyond imagination, then he ended up in a place where he could talk about that.

We said, “How do you feel about yourself? Are you ready to talk to us? Do you want to go to a therapist?” One of the things that Fortune has developed, which is one of the most important units is called a Better Living Center, where we have therapists and group therapy. It’s a population that is resistant to it, “I ain’t crazy. I am going in.”

The best ambassadors for that are their brothers and sisters who have done time with them and said, “It ain’t a weakness. It’s a sign of strength. Do what I did.” We don’t have to recruit people. They recruit each other. Therapy may not be for everybody, but it isn’t bad, and so is NA or AA. You deal with all those. Bob Brown, an old timer, years ago said, “We suffer from the crocodiles of our dreams.”

I said, “What a vivid image.” Bob said to me, “When I look back on my childhood, I don’t ever remember being hugged. I don’t remember the sun shining. Obviously, the sun shined, but I was always locked in a closet somewhere.” That little boy of 5 and 6 can’t process all of it. Do you know who Darryl Strawberry is, a great baseball player?

I will tell this story because older guys appreciate it. Darryl Strawberry is a great baseball player for the Mets. I loved him. He looked like the man everybody wanted to be. He was 6’6. He was a handsome African-American. He had a great build and was a great ball player. You could see that his teammates loved him. He was a leader in every sense of the word. After he finished playing ball, he became a user of drugs. In a book or an article that I read, he told the story that when he had a home run, he was rounding the bases and 50,000 people were yelling, “Darryl.”

He said to himself, “What would they be yelling if they knew who I was?” which is an incredible statement because who he was was this idol of millions and adored by the people up close to him. He told the story all through his child that he had a father who told them, “You’re nothing. You’ll never be anything. You’re a piece of crap.” When you’re 5, 6, and 7, and the man who’s in charge of your life said that, you don’t process that. You become that if you don’t have an adult, a grandmother, or somebody who is saying, “You’re special. You’re beautiful. You are wonderful.” Darryl grew up with all those talents, not knowing that he had them. Now, he does.

Everybody needs somebody.

I’m in WBAI in New York, Saturday mornings from 8:00 to 10:00 and Mondays from 10:00 to 12:00. I play music. I interview people. I read books, and talk about books and movies. I talk about a lot of things at the Fortune Society. It’s something I’ve come to understand. This may be my closing. Looking back many years as Fortune has grown, I am proud of the people who have come after me, how they’ve shaped it, and all that.

My great gift at the beginning besides the fact that I was a publicist, I knew how to work the media and all of that was that I didn’t know anything about the system. I kept asking why it didn’t work. I found that people, especially guys who had done times, everybody knows this, people don’t know that. You have to visit a jail. You say, “My God.”

I remember that before the Attica riot, they didn’t talk to the inmates. They tapped the stick and that meant go or stop. The Black inmates will tell you that they referred to them as nigger sticks because they hit them with that. That’s how they referred it to. When you go to a place like that, you hear and see that, and then when you become politically sophisticated and you go to ACA, American Correction Association Convention, into the field house, see the vendors and the big money that’s being made, and the people who have an investment in keeping a prison going, you find out why effective programs are cut. If they’re working and people don’t come back, there’s a loss of money. Not only the loss of jobs by the correction staff and the vendors, but that’s also where the big money is.

When the Rockefeller Drug Law passed, around the country, prisons and jails were built and the steel companies, cement companies, and the people that make flammable blankets and toilet seats weren’t selling them by the twos. They were selling them by the 10,000s to new institutions. Remember that movie, Follow The Money, a Tom Cruise movie?

You can learn a lot. My wind-up is that. I say this because I pass it on to people. Reach me at FortuneSociety.org. I’m retired and old. There are younger people doing it all. If you have questions and information, I’ve developed the art of passing it on and referring to it. That’s what you do when you’re in your twilight years.

We now have a staff of 400. At least 200 of the people at Fortune probably don’t know our history. Can I say one more thing?

You laughed at something I said. One of the things that people who come into Fortune have always said is that they are surprised that there’s much laughter. Laughter is healing. It creates an atmosphere where people can laugh. It also creates trust.

Important Links

About David Rothenberg

David Rothenberg’s life has centered on theater, social activism, politics, and a tireless focus on advocating for the lives of those impacted by the criminal justice system. In 1967, David Rothenberg produced a play called Fortune and Men’s Eyes that revealed the horrors of life in prison. This inspired him to establish The Fortune Society (Fortune). In its 50 years, Fortune has become one of the leading reentry service organizations in the country, serving nearly 7,000 formerly incarcerated individuals per year, providing a wide range of holistic services to meet their needs. Fortune has also secured a position as a leading advocate in the fight for criminal justice reform and alternatives to incarceration. In September of 1971, David Rothenberg was one of a small group of courageous civilian monitors brought in to Attica at the request of the incarcerated individuals who were fighting for their human rights – an incident that ended in tragedy, but showed the world the horrors of the criminal justice system in the United States.

David Rothenberg’s life has centered on theater, social activism, politics, and a tireless focus on advocating for the lives of those impacted by the criminal justice system. In 1967, David Rothenberg produced a play called Fortune and Men’s Eyes that revealed the horrors of life in prison. This inspired him to establish The Fortune Society (Fortune). In its 50 years, Fortune has become one of the leading reentry service organizations in the country, serving nearly 7,000 formerly incarcerated individuals per year, providing a wide range of holistic services to meet their needs. Fortune has also secured a position as a leading advocate in the fight for criminal justice reform and alternatives to incarceration. In September of 1971, David Rothenberg was one of a small group of courageous civilian monitors brought in to Attica at the request of the incarcerated individuals who were fighting for their human rights – an incident that ended in tragedy, but showed the world the horrors of the criminal justice system in the United States.

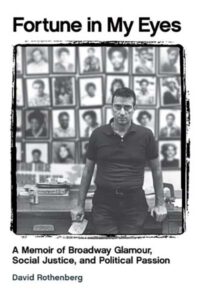

He is a former member of the NYC Human Rights Commission and was appointed as Advisory Counsel to the NYS Commission on Human Rights in 1984. He has frequently testified about the criminal justice system before the U.S. Senate and U.S. House of Representatives – and in State and City governing bodies around the nation. With the help of Fortune participants, David created, wrote, and produced the play The Castle, which has been performed off-Broadway, on college campuses, and in prisons. David has been featured in various media publications, such as Democracy Now!, The New York Times, The Huffington Post, and Newsday. His memoir Fortune in my Eyes was published in 2015. Now in his mid-80s, David continues to volunteer at Fortune every week, actively seeking out new ways to highlight the issues and needs of the formerly incarcerated through theater, art, advocacy, conversation, communications, and innovative programming.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join the Prison: The Hidden Sentence Community today:

Leave a Reply