Incarceration can take away hope’s wings, but a helping hand can mend them, allowing hope to soar again. In this compelling episode, join us on a journey through over five decades of unwavering advocacy with Barbara Allan and David Rothenberg. Discover the inspiring story of their transformative efforts, leaving an indelible mark on the lives of those formerly incarcerated and their families. From the early days of their commitment to the present, witness the creation of a lasting legacy built on compassion, resilience, and the profound belief in changing lives, one person at a time. This is a testament to the enduring power of dedicated individuals who have shaped the narrative of redemption and support within the realm of criminal justice. Tune in to experience the heartwarming narrative of Barbara and David’s impactful journey.

—

Listen to the podcast here

Legacy Of Transformation: Barbara Allan And David Rothenberg’s 50+ Year Journey Changing The Lives Of The Formerly Incarcerated And Their Families

This is Julia Lazareck to season four of the Prison: The Hidden Sentence. As the Founder and Host of Prison: The Hidden Sentence and Cofounder of Prison Families Alliance, along with the remarkable Barbara Allan, I’m not only dedicated to sharing these compelling stories but also passionate about raising awareness about the effects of incarceration in families as well as providing a support system for these families and youth.

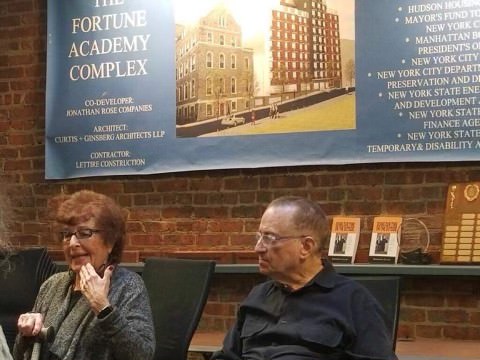

I have an extraordinary tale to share, one of an unexpected friendship that has spanned many years. Despite their diverse paths, Barbara Allan and David Rothenberg not only crossed each other’s journeys but embarked on a collective mission that has stood the test of time. Each contributes in their unique way, their paths intertwined, and the impact of their shared endeavors has only grown stronger.

These stories are not just narratives. They’re a testament to the resilience, friendship, and a legacy that deserves to be read. I’ve had the privilege of interviewing each of them separately, and now I bring them together to tell a story you won’t want to miss. Come along with me as we read this unexpected partnership that holds the potential to transform how you view incarceration and the prison system. Sit back, relax, and get ready to be inspired by a story that transcends time and transforms lives.

—

David and Barbara, I’m honored to have you both here with me. Your stories are powerful. I want to start with David on how you got started in all of this because it’s not something we choose. It’s something that in life happens and puts us on this path. Let’s start with David, and we’ll go to Barbara.

Julia, you want to know how The Fortune Society began, which was back in 1967. Nothing was planned. It was one of the most unlikely beginnings of an organization. I was working in the theater and knew bupkis about prison. I didn’t know anything. Old movies were my reference. I knew the theater. I read a powerful play called Fortune in Men’s Eyes.

I learned that it was the story of a young boy going into a juvenile facility who was gang raped on his first night. It turned out to be the story of the playwright, John Herbert. I wanted to get it on, and I couldn’t get anybody else to produce it. I said, “I would produce it.” We cast it. The actors wanted to validate their roles as prisoners. We arranged to go to Rikers Island, the city jail, which was my first visit to a jail in 1966.

When I went in, I was overwhelmed by the sense of futility. It was a juvenile facility. They were all teenage boys sitting around staring into the air. I thought, “Whatever brought them there, how are they going to be any better as a result of this?” Instinctively, I said, “This is an exercise in institutional futility.” We have this whole institution. I was angry at myself that I was unaware of what was going on, and it had been for centuries.

The play was produced. After it opened, one night, a professor brought a group of students and asked if there could be a dialogue with the actors afterward. That was right up my alley. Somebody in the audience challenged the play’s validity. From the back of the house, a man stood up and said, “None of my years in joints like this counts for anything.”

We invited him to come on stage, a man named Pat McGarry. The following week, he came back with a friend named Clarence Cooper, and we started these weekly Tuesday night meetings after a play. One night, the New York Times sent a reporter, and the headline was, “The Drama Continues After The Curtain Falls.” It said that we do this every Tuesday night.

The following Tuesday night, after the house, there were guys who had done time. We had to go and have coffee afterward. I remember this clearly. I said to the guys, “They all were working, but they all had a lie to get their jobs. They all had houses, but none of them could sign the lease. It was either a wife, a girlfriend, a mother, a boyfriend, or somebody. When does the punishment stop?” They all yelled, “Never. It’s for life.” I said, “Unfair.” One other Tuesday night, I said, “These guys kept coming back because they had a need to share their rage at their prison experience. We have the nucleus of an organization. We could change the world and all these placebos’ perception.” We called it Fortune Society from the title of the play.

Sixteen people gave me $2 to open a bank account of $32. I thought that it was going to be an advocacy organization, and I would remain working in the theater. As we arranged for speaking engagements, guys went on radio and television, and other men kept coming to my office thinking we were this thriving organization asking for jobs, housing, and all the things men coming out of prison need. I keep saying men because it was a couple of years before women came for multiple reasons.

We became a service organization. From that little one room with three people in it many years later, and I’m long retired, it’s an organization with 500 staff members and six residents for housing and services that are one-stop. Everything’s covered. One of the things that happened in that first television show was that we got lots of letters, and one of them was from Barbara Allan.

Which show was that?

It was The David Susskind show played in March of 1967.

Barbara, what happened when you saw that show?

I watched it with deep trepidation because my husband was incarcerated and this was a show that was going to talk about people who are incarcerated. It was 11:00 at night, and I was usually sound asleep by 11:00. I had two small children, and I had to take care of their needs, but something compelled me to watch the show. As a result, I wrote David a letter. I said, “I was doing my time on the outside.”

David invited me to come to a meeting they were having. As a result of the show, a lot of people responded. I’m holding my breath and holding hard onto my father’s hand. We walked out the door. We were going to go into a venue with lots of ex-cons. Back then, that’s what we call them. I walked into this room, and I saw the most wonderful people. I met David, Kenny Jackson, and Marjorie O’Keefe. They became my extended family.

I want to say that before I go any further if it had not been for meeting David and all those wonderful people at Fortune, I am not sure what would’ve happened to me because I felt isolated, frightened, and stigmatized. Here, I met people who hugged and welcomed me. I was even asked to go on a speaking engagement. I believe the first one, David, was a professor. You took me to his house. He had some students there. The last name began with an M and I don’t remember his name.

I spoke and talked about my feelings and the difficulty of having a loved one incarcerated. It was such a welcoming environment. I found my niche. As I remained with Fortune, when someone called the office and asked for information about a loved one, David would tell them, or whoever answered the phone, but mostly David, would give them my phone number. That’s how my phone number started getting written on the walls.

They’re on the walls of the jails and prisons in New York because people call. When did you start your organization, Barbara?

It was started as a grassroots organization. When I was visiting my husband in the county jail, he would tell me to talk to people who were visiting down the aisle. He said, “Look to the left, Barbara. You see that family two spaces down.” We talked on telephones with plexiglass. I would turn to the person and say, “How are you doing?” We bonded.

The only people I felt comfortable with were the people on those lines in the visiting room and the people I met through Fortune. It was a relief. They understand me. We started having coffee. We started going to my house and expanding the number of people. It was not intentional. People started talking and relating to each other. Until one day, we decided to become a 501(c)(3) and formalize it.

That was the beginning of Prison Families Anonymous, one of the predecessors to Prison Families Alliance. You and David kept your communication. After David was working on The Fortune Society and you were working with the families on the outside with Prison Families Anonymous, how did you guys work together and continue supporting each other?

It was easy. It was natural. Somebody would call, and there would be a family situation. Barbara was the obvious resource. As Barbara was speaking, it suddenly dawned on me. At Fortune Society, we have education and housing, but it was the people who came in that defined the needs. We didn’t say, “This is what we need to do.” People came in, and they wanted jobs. We had to set up a job unit. People needed housing. We had to find the resources.

In the same way, when people called who were relatives and they had specific needs, they called Barbara. It’s all organic. The people in need should find what we all should become. Prison Families is like a tributary almost of The Fortune Society. It became an obvious place of source of reference. A mother would call and say, “I don’t know how to get up there. It’s difficult for me to travel. Call Prison Families and find out if there’s a carpool.” These are basic things, and there’s no end to them. You can never be prepared for when the next problems arise.

That’s how we operated as the needs became obvious. When we started, we did not want to go for funding because we did not want to have other people tell us what to do. We didn’t even have a board of directors. We called it a group council. It was our family. It was families helping families. When I spoke with The Fortune Society, I did feel I was a part of it. I never separated emotionally from The Fortune Society. Even now, when I go out speaking, I wear The Fortune Society hat because we are.

As David said, the people who came to him were damaged by the system. Our people were the collateral damage of the criminal justice system. When our kids said they wanted a group for the children, we started a children’s group. When men started coming out, and at the time, it was almost exclusively men. When they started coming out of prison, we had couples meetings because we thought it was important that they learned to adapt to one another. It’s the same philosophy. It is parallel to The Fortune Society.

Neither Fortune nor Prison Families should exist. What we do is what the system should be doing. They spend billions of dollars in county, city jails, and state and federal prisons that destroy the human spirit. What we and Prison Families have done is find that which connects with people. If the system was healing rather than preoccupied with punishment, we would be saving lives not only the lives of the incarcerated and their families but of the public, which suffers from the failures of the system, the people who become victims of a failed system.

I hope a lot of people read this. I want to go back to what you said, David, the first time you walked into the jail and you saw those young men. Part of you were mad at yourself for not knowing about it. That struck me because a lot of us are like that. Barbara can agree, and myself too. Before my brother was in the system, I had no idea. That’s why I’m hoping that this show and people who read it become aware. When people become aware, we can start that healing. What you guys are doing is important.

The high walls are not only to keep prisoners in but to keep us out and uninformed. We have an ATI program. That has evolved over the years because a judge sent a teenager to me who was possibly going to jail, but the judge said, “He hangs out with you guys.” Jose Torres came, and his whole gang was with us within a month. They are teenagers, 17 and 18 years old.

One of the things I’ve learned from the teenagers, many of whom had been on Rikers, I remember always asking the kid, “Why are there always fights in the juvenile section?” We have the same youngsters. We never have fights. When they come to Fortune, they have classes. That determines their educational levels. We have group wraps and field trips. They’re doing things. I said, “Why are there always fights at Rikers Island?” One kid said, “It breaks up the boredom. They don’t do anything.” Joanne Page said, “Death by boredom.” it is how she defined Rikers Island. They have interests. We have to want them. This is a societal problem. Our need to punish is greater than our need to solve our problems.

Our need to punish is sometimes a societal problem. Our need to punish is greater than our need to solve our problems. Share on XI went to Rikers Island as a student. I was minoring in Sociology. We took a trip to Rikers Island. This is back in the ‘50s. I said to myself, “We are keeping people locked in cells.” I was aware, even as a student, that this was unacceptable. I went on with my life until it hit me. One of the things I’d like to emphasize is that we were able to make changes. David spoke of the changes in people’s lives by going to The Fortune Society. I worked with Fortune to get rid of the archaic visiting and implement contact visits in New York State.

When Jim went to prison, there were no contact visits except in Sing Sing, which you all know about if you’ve ever gone to an old movie. That was reception. Everyone in the system came through Sing Sing, and they had contact visits, but no other prison in New York State did. With the support and help of The Fortune Society, and I’m talking about Kenny, Mel, and many of the people who were supportive of us, we managed to change that. There are now contact visits in every prison in New York State. It didn’t come easily. We did a lot of fighting and a lot of going up to legislators. I was told by a warden that there would never be contact visits in my lifetime. I like to say that. I’m still alive, and he’s not. That wasn’t nice.

One of the other things that we all fought about was the idea when I learned about solitary confinement. I visited several solitary confinements. They’re horrible to see. When you meet guys and women who have come out, and somebody tells you they did five years in solitary confinement, you meet wounded people. I’ve often said to people who say, “What do you do when somebody acts out in prison?” I say, “Lock yourself in your bathroom someday for 48 hours with no television, radio, or phones. See how that prepares you to function. If you don’t go stalk, you are steering mad.”

New York City Council passed an anti-solitary confinement fine. The mayor is threatening to veto it. Political people have to visit solitary confinement. They have to talk to men and women who have spent years in confinement. We’re not only talking about the humanity in the jail. When somebody comes out of prison, and they’ve done 5 or 6 years in solitary confinement, they’re a threat to the community because they’re angry and they feel that society has allowed this to happen to them. They’ve never confronted why they were there in the first place. You have people in prison who have had traumas in their childhood that have sent them off the rails and never confronted them.

One of the things we found at Fortune is that people are in an environment that gives them the opportunity to start trusting. Trust is the tough part because society has abandoned and abused them. In many cases, they’re 4, 5, and 6 year olds. They don’t process it. We’ve talked to guys, “When you were in juvenile facilities, what happened when you got out?” They all said, “We went to prison. That’s what we were prepared and trained for.” There were answers. We have to want it badly enough.

What are some of the things that we can do? Apparently, they’re not getting what they need in the prisons. Is there something that we can do in the schools? What can people who are reading this do?

I went to a candidate’s announcement. He is running for Mayor of Jersey City. He’s a friend of mine. He said that he has programs to get every kid literate. By the third grade, they can read and write. He said, “If they can’t, if they’re going to end up in programs like The Fortune Society because they can’t compete.” A lot of the kids can’t learn to read and write, not because they’re not smart, but because they come from such troubled homes that they can’t focus when they’re in school. They miss school because they’re from troubled domes or homeless, living in shelters with their family.

I thought it was fascinating. It sounds like a quantum leap. Being able to read and write means you can compete on one level. It doesn’t undo the traumas, but it gives you a headstart in a lot of cases. Those people who are not ready to tiptoe into the criminal justice system can do a great deal about education in their hometowns, especially in poverty areas and high-crime areas. Find out what’s happening with the children in those schools. What are the size of the classrooms? Go to a good private school and see what the curriculum is. You don’t have to create anything new. Bring that into the public schools.

It’s important to start with the youth. Barbara, go ahead.

I was a primary school teacher. I taught because I loved working with the children whom the other teachers found troublesome. I know a lot of hugging. I can’t do that anymore as a teacher, but I had a lot of children sitting on my lap and hugging them. That helped because they weren’t getting that at home. The field of mental health has to step in, even talking about solitary confinement. Many people who are in solitary are there because they’re non-compliant.

The reason they’re non-compliant is because they have mental health issues. We have a terrible system out here for dealing with that. People cannot get the help they need. They deny them financially. It’s a serious problem. I also work with NAMI, the National Alliance on Mental Illness, because it affects many of the people that we work with. There are solutions. I often talk to David about the ODTC program. When Mike called, it brought it back to my mind, but wasn’t that a successful program that cost a lot of money?

We have a terrible system of dealing with people who cannot get help. Share on XWhat was it?

Clinton Prison, which is right next to the committee.

It’s the Diagnostic and Treatment Center.

Do you want to talk about it, David?

It was an excellent program that McGill University brought into a maximum security prison in New York State. They took and they wanted guys who had long records, not only of child facilities but problems of violence. Their recidivism rate was incredibly low. We would start meeting guys coming out of the Diagnostic and Treatment Center. They were motivated more than anything else. They had a sense of why they did what they did and what tools they needed not to repeat it. That program was defunded and eliminated because anything that has a low recidivism rate threatens the creation of prisons.

One of the things they talk about is the prison industrial complex, the fact that there are large industries. I went to an American Correction Association Conference. The most interesting thing was the field house where all the vendors were. You saw what an investment big business had, not in maintaining, but in building architects and construction companies, cement people, and steal people, to say nothing of food, inflammable blankets, toilet bowls, and a range of things selling by the thousands, making contracts deals at that fieldhouse. I was overwhelmed by the amount of money to sustain.

What came out of that were things like the Rockefeller drug law and other laws, things that were not against the law, that they made laws. There was a story in New Yorker Magazine about the number of people who were doing life for murder when they weren’t even at the scene of the crime. One was two boys who broke into a store. The cop shot and killed one kid. The other kid was tried for murder because the law said the shooting would’ve never happened if they didn’t break into it. This kid got life in jail.

I don’t want to make this regional, but in a lot of Southern states, the state legislators are easily gotten to because of no accountability. They make laws about things that kids might have been arrested for participating in a robbery and getting six months or a year of probation and were tried for murder because there’s a law that says, “You were part of the scene.” There was another man who was six miles away in handcuffs when an automobile crashed into somebody, and the pedestrian died. He was charged with murder. It’s big business.

People are hesitant about getting involved with criminal justice because of understandable fears. Education and mental health are both closely related to the criminal justice system. Concerned citizens can involve themselves in those arenas if they’re not ready to step forward about the prison system, which is an exercise in futility.

It’s important for people to read your stories and what you’ve done. You both are trailblazers. What are some of the most impactful things? You’ve been telling us a lot about how you started, how you met, what you’ve done, the changes you’ve made, and the impact you’ve made. However, if you can pick out one thing or person that you’ve seen as a turning point, that you can share.

Barbara, I’ll start with you. You’ve spoken about people that you’ve had in your house that you would never think that you would’ve been friends with. I interviewed David and Barbara separately, and you can read their stories on Prison: The Hidden Sentence. I wanted to bring them both together because of how impactful and how connected they are. Barbara, do you want to share a story of something you’ve seen or happened that changed your mind or opened your eyes?

You’re looking for people who have come to my house, and many thanks to The Fortune Society with Kenny. When someone didn’t have a place to go, it was either David’s living room couch or me. I had a five-bedroom house at that time. I got a lot of people coming to my house. When I think back at it, I had two babies. I had two small daughters. I did take a lot of risks, but I never did anyone harm my children or me. It was something I did.

Could you do that now?

When Jean went to prison, I had nowhere to turn. I had no idea how to navigate the system. There is one thing that David taught me. He said it a long time ago. Julia, you called a lot of what I say barbarism, but they’re not. They come from people like David. While you are waiting to change the world, if you help one person at a time, it is the way you change the world. That’s my philosophy. Whenever I get a phone call from someone who says thank you, I feel better. That’s our whole purpose of existence, at least mine.

That’s an intro to my answer because I was on a panel once, and some guy working in the system said, “How would you reduce crime?” I said, “You do it one person at a time.” He said, “That would take a long time.” I said, “You’re managing to destroy one at a time. We can reverse that. The one at a time over a period of weeks, months, or years become hundreds.”

If you want a single story, none is more vivid for me than Casimiro Torres, who came to the castle. He had been abandoned as a child. He came in youth houses. He says that at the age of nine, he started drinking wine and taking weed because that’s how I managed the pain. He’s one of the people who said when the juvenile system got rid of him. I said, “What happened?” He said, “I ended up in prison.” He came to the castle.

We have community meetings every Thursday night. You’ve been to one, Julia. I looked at Caz, and I thought, “The body language is the sense of alienation.” He later told me, “When you’ve gone from prison to prison, and you arrive at a new place, you remain silent. Look out and find out what’s going on here.” I watched his body language and appearance change. When he started to talk, I realized that there was a person there. It’s a smart person. We became good friends. His two kids were raised through Fortune, not by fortune, but they became part of us. His wife, Ali, is a part of us. He works now at Fortune. He’s been out of prison for several years. He thought he’d never ever have that transition.

I tell you this story, Julia, but I hesitate at criminal justice conferences because when you tell a story, they say, “That’s an anecdote. We have the statistics.” I once said to a man named James Q. Wilson, who was the first one through that, “My anecdotes add up to all the statistics that you throw out. It’s about people. I could give you endless anecdotes, but one person represents a lot of people who want change and are hungry for change. They have to go into an environment that nurtures that possibility.”

I love these stories. There are many more stories. That’s why I wanted to bring the two of you together. You guys have made such changes and are such beacons and have such a legacy in what we can all do. Unfortunately, we have these organizations. It’s unfortunate that we have to, but it’s fortunate that there are many people out there who have seen what’s happening. They want change that is making changes.

Barbara and I are working together with the Prison Families Alliance and the families on the outside because we know that by empowering, educating, and supporting the families, they can better support their loved ones. When people are at The Fortune Society, and like David said, “Barbara has been there a lot.” I happened to be able to attend one of the meetings when I was visiting Barbara earlier. It was amazing seeing these people sharing. You could see them blossoming. You could see them seeing that there was a future that they might not have had.

That’s why it’s important that we read stories from you guys and bring in new people, new blood, fresh blood, and fresh ideas so that we can keep things going and make these changes. With a larger voice, we can get things changed in the criminal justice system or the carceral system. Change has to happen. It is big business. We know that.

I worked for a software company that did law enforcement software. I would go to conferences. David, I saw a lot of what you said. There are many big businesses in there selling to the jails and the prisons to keep them going. If we can get programs in there and funding so that we can have these programs that we know work, it will help many people.

I appreciate both of you for your time being here and spending time with me. We got things going. I always like to end with what we can tell the families because Prison: The Hidden Sentence was started because the families on the outside are serving the sentence with their loved ones. We don’t talk about it, and we need to talk about it. What can we tell the families to give them hope? Barbara, I’ll start with you, and we’ll conclude with David.

We can tell them they can’t get through it. They will get through it one day at a time. They are important people. They have a right to contact the facility to have their voices heard. I’m a believer in speaking out. I laughingly say, “I carry a soapbox in my car.” I feel it’s important that our stories be told and understood by people who are not affected. Our families have the power to do that. By doing that, they empower themselves, and they have the ability to make a change in the system.

Our stories must be told and understood by people who are not affected. Our families have the power to do that. They empower themselves and change the system. Share on XI’m saying to someone, “You’re not alone.” I’m providing the reality that they’re not, and you’re there for them. You’re a phone call away because the sense of isolation of people who have loved ones away is overwhelming. Often, they can’t talk to the people closest in their lives, their own relatives, and their own friends. They suddenly need a new family or a surrogate family. Both Fortune and Prison Alliance can provide that, but we make sure that they know they’re not alone.

When somebody is released, it is important to have the programs inside the prison and with the families on the outside. Can you talk at a high level about reunification or what you’ve seen when somebody comes out, and their family participates with them at Fortune, and how that helps and supports them if they have that family?

The reality is half the people who come out don’t have anybody to come out to, which is sad. Fortune becomes the surrogate family. I’ve gotten to know some relatives who are excited about a relative coming out. I think, “Let him go slow. No parties and big celebrations.” The tendency is to have a big party. The only one who’s not sharing in the party is the man who’s done 18 or 20 years because he feels isolated. That’s not for everyone. For the most part, you have to let people go, find what their pace is, let them go at their pace, and make it possible for them not to be afraid to ask questions about new technology, feel uncomfortable in crowds, be awkward around children, and things that they have not had for years.

When I came to The Fortune Society for that meeting, a woman brought her brother. She was talking about how she wanted him to be a part of this. He was sitting there. His eyes were looking far away, like he wasn’t there because he had gotten released. As she and the people from Fortune Society talked to him, I saw his eyes. The glaze was removed, and it was almost like a relief. He felt like there was hope.

They knew what he was going through. He had been there.

Reentry has to start at the time of arrest. That’s what our families need to know. Whether the person is away, I believe in bringing reality to them. If something is happening at home, I wouldn’t make a big deal of it. You could let that person know. The children have measles. I’m having difficulty paying my bills. This is real life.

Sometimes, people inside, from what I’ve heard, have a fantasy life. I heard from someone way back, David, that when they’re inside, they talk about the big Cadillacs and the girls they have on the outside. That’s how they relate to one another. When the family comes in, we are the reality. We have to start from the minute they’re away.

We keep them a part of the decisions. People want to reach out to the Prison Families Alliance. They can go to the website PrisonFamiliesAlliance.org. They can email at Connect@PrisonFamiliesAlliance.org. David, if somebody wants to reach out to The Fortune Society and learn more about it, what is your website?

There is a website. It’s www.FortuneSociety.org.

I want to thank you both for your time, and I appreciate everything you’re doing and done. You set the bar for the rest of us to keep it going. Thank you.

Thank you, Julia.

Important Links

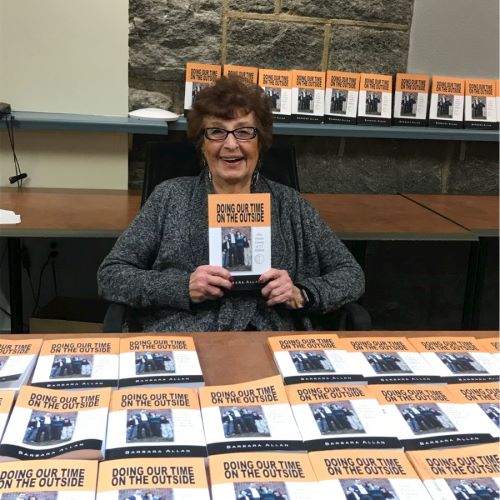

About Barbara Allan

Barbara Allan’s life took an unexpected turn in 1966 when her husband’s imprisonment thrust her into a world she had never known. As a devoted schoolteacher, wife, and mother with no prior involvement in the criminal justice system, she grappled with feelings of isolation and confusion. Yet, in her search for solace, she discovered a community of individuals enduring similar pain.

Barbara Allan’s life took an unexpected turn in 1966 when her husband’s imprisonment thrust her into a world she had never known. As a devoted schoolteacher, wife, and mother with no prior involvement in the criminal justice system, she grappled with feelings of isolation and confusion. Yet, in her search for solace, she discovered a community of individuals enduring similar pain.

Driven by her own journey, Barbara became a beacon of support by founding Prison Families Anonymous. Over the years, she has touched the lives of thousands, offering guidance and empathy to those navigating the complexities of having a loved one incarcerated. Her profound experiences culminated in the memoir “Doing Our Time on the Outside,” a testament to resilience and the human spirit.

Barbara’s advocacy extended far beyond personal narratives. She has addressed legislators, senate committees, and commissioners, shedding light on the challenges faced by families affected by incarceration. Her impactful writings, including a published piece in the Congressional Record, have amplified the voices of those often unheard. Barbara co-founded Prison Families Alliance (PFA) with Julia Lazareck.

PFA is an organization that extends its reach across the United States, providing vital support groups for anyone who has a loved one in the carceral system. As a co-founder, she champions a cause close to her heart, recognizing the hidden sentences served by families outside prison walls. Barbara Allan stands as a compassionate leader and advocate, tirelessly working towards positive change and offers hope to those families on the outside the bars. Her unwavering dedication continues to pave the way for support and understanding in a challenging landscape.

About David Rothenberg

David Rothenberg’s life has centered on theater, social activism, politics, and a tireless focus on advocating for the lives of those impacted by the criminal justice system. In 1967, David Rothenberg produced a play called Fortune and Men’s Eyes that revealed the horrors of life in prison. This inspired him to establish The Fortune Society (Fortune). In its 50 years, Fortune has become one of the leading reentry service organizations in the country, serving nearly 7,000 formerly incarcerated individuals per year, providing a wide range of holistic services to meet their needs. Fortune has also secured a position as a leading advocate in the fight for criminal justice reform and alternatives to incarceration.

David Rothenberg’s life has centered on theater, social activism, politics, and a tireless focus on advocating for the lives of those impacted by the criminal justice system. In 1967, David Rothenberg produced a play called Fortune and Men’s Eyes that revealed the horrors of life in prison. This inspired him to establish The Fortune Society (Fortune). In its 50 years, Fortune has become one of the leading reentry service organizations in the country, serving nearly 7,000 formerly incarcerated individuals per year, providing a wide range of holistic services to meet their needs. Fortune has also secured a position as a leading advocate in the fight for criminal justice reform and alternatives to incarceration.

In September of 1971, David Rothenberg was one of a small group of courageous civilian monitors brought in to Attica at the request of the incarcerated individuals who were fighting for their human rights – an incident that ended in tragedy, but showed the world the horrors of the criminal justice system in the United States. He is a former member of the NYC Human Rights Commission and was appointed as Advisory Counsel to the NYS Commission on Human Rights in 1984. He has frequently testified about the criminal justice system before the U.S. Senate and U.S. House of Representatives – and in State and City governing bodies around the nation.

With the help of Fortune participants, David created, wrote, and produced the play The Castle, which has been performed off-Broadway, on college campuses, and in prisons. David has been featured in various media publications, such as Democracy Now!, The New York Times, The Huffington Post, and Newsday. His memoir Fortune in my Eyes was published in 2015. Now in his mid- 80s, David continues to volunteer at Fortune every week, actively seeking out new ways to highlight the issues and needs of the formerly incarcerated through theater, art, advocacy, conversation, communications, and innovative programming.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join the Prison: The Hidden Sentence Community today:

Leave a Reply