How do you tell a child that mommy or daddy is in prison? Julia Lazareck sits down with Dr. Avon Hart-Johnson, the author and Co-founder of DC Project Connect, who explains how parents or guardians can tell the truth about incarceration when talking to children. Dr. Avon points out the importance of understanding the adverse effects of incarceration and how adults can avoid further emotional and mental damage to children using resources such as children’s books and better communication. She also highlights how adults in the family can significantly affect how they can mold a child’s behavior, as children usually begin modeling behaviors exhibited by their parents.

—

Listen to the podcast here:

Tell Your Children The Truth About Incarceration With Dr. Avon Hart-Johnson

I’m here with Avon Hart-Johnson, PhD, who’s the President and Founder of DC Project Connect. It’s a nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization whose mission is to provide crisis support, advocacy and psychoeducational services for families affected by incarceration. She chairs the International Advocacy and Action Coalition working group for the International Prisoner’s Family Conference Organization. She is a board member and Vice President for the International Coalition for Children With Incarcerated Parents. She’s co-authored the Mass Incarceration Continuum white paper, which is cited as the human rights issue of the 21st Century. Dr. Johnson has also authored four children’s books that she’ll discuss with us.

—

Dr. Johnson, you’re doing so much to raise awareness and advocate for change in the prison system, how did you get started in all of this?

First of all, thank you, Julia, for having me, for all the work that you do, and for using this platform to talk about such an important topic. My background and my PhD were in forensic psychology and human services counseling. I conducted research on how families could be adversely impacted by incarceration. What I found out through my interviews, that not only were the parents, the caregivers, the spouses, and the girlfriends, or the family suffering from the adverse effects of incarceration, but specifically, it troubled me that children were actually suffering, of which I thought to be a form of grief.

While I was doing my research, I said to myself that one day, I’ll return back to that topic. I authored self-help books for adults in dealing with incarceration based on my research study and on my findings. I then conducted a study along with another principal researcher, Dr. Jeffrey Johnson, in the United Kingdom. We were visiting United Kingdom prisons and trying to understand better how these programs were favorable to the family and the children.

We found out the ways in which they created these warm, friendly, colorful spaces for children. Because the common denominator is that if you treat children with dignity and respect, when the parents come in those areas, you will treat them with dignity and respect. I found it quite remarkable. One of the things that stood out to me, which leads to the creation of the children’s books, is we kept hearing this repeated theme. When they visited these community centers that have play spaces and lovely areas like reading spaces for the children, children, who were young, walked in those spaces and actually started to believe they were in a community center, rather than a jail or a prison. What happened is, this provided a platform for the parents to change the truth, some would call it a lie. They started to tell the children, “You’re at your daddy’s work. You’re at the community center.”

Children begin modeling their behaviors from the behaviors exhibited by their parents. Share on XWhen I left, I said, “They’ve done wonderful work,” but what happens when a child learns to read? What happens when children find out otherwise? What does it do to the trust factor? About two years later, we put together a research study of which I was the principal researcher. We wanted to consult with caregivers and ask them, “How do you communicate with your children about parental incarceration?” We considered the caregivers to be the biological parent or not, stepparents, auntie, uncle, grandparents, anybody that fit that criteria of taking care of children, we wanted to know how they communicated with the children.

The second part of that research focus was how, if at all, do you believe that stories could help you communicate those sensitive topics? I feel that was a wonderful learning experience for us. We learned so much from the research. In addition to the emotions that the caregivers were feeling, what we found out in the research, and it was quite fascinating, is something that we called a mirror effect. We found out that children began modeling their behaviors from the role model behavior exhibited by the parent. Whether the parent modeled using their emotional intelligence or using patience, being hopeful and being optimistic, children were behaving that way.

We found that in some cases, even the grandparents were a little bit angry because they were taking care of kids, their children’s children. Instead of being able to retire, they had to take care of their children’s children, plus, they were disappointed in the behaviors that led their children to be incarcerated. There was this underpinning of anger. I remember this one grandmother, in particular, she was saying she could not understand why her grandson was so angry, why he acted out in school, and why he had tantrums.

I’m thinking, “He’s getting that anger because he’s seeing that modeled as a way of problem-solving.” Parents have to be mindful of not only managing their own emotions but how those emotions might translate and be projected upon their children. That gave us this notion of making sure that when we developed our children’s books that we made sure that they had the underpinning of the emotions, the situations, and scenarios that we saw showing up in the research. That was quite fascinating.

That is where we came about with the themes for the children’s books, such as Baby Star Finds “Happy”. That is a book about a little person whose mom went to jail. Now, dad is in the role of cooking and caring for the kids and having to explain what happened to mommy. A non-traditional story, one of which we have not found out there in children’s literature. We then have Jamie’s Big Visit. That is a book that chronicles Jamie’s experience when he is ushered out of the house and taken to grandma’s house during this family crisis. He doesn’t know what’s going on. Finally, mom sits him down and has the big talk and says, “This is what’s happened to dad,” whom he admired. “This is how we prepare for the big visit to the jail or prison.”

One thing I want to talk about briefly, I used the word Big Visit on purpose when I authored that book. When little people go and visit jails and prisons, the interesting thing is that from an adult perspective, we may be used to seeing or we can adjust to seeing someone with a big key ring, loud clunky doors, the great big facade of the prison, the big counters of which they have a reception counter. Some of them are actually towering over some adults where before you go through the metal detector and all of that, it’s a scary experience because everything seems to be big to little children. The idea in Jamie’s Big Visit is to focus on a lot of the big things that Jamie sees from the eyes of a child. The big trees, the big mountains, and the big prisons, and it gives a platform for parents to have a discussion with their children.

That’s the long story in terms of the backdrop of how we got started. We do work in the halfway houses in Washington, DC. We work with the parents. From those discussions during our life skills programming, we have heard the tough time that parents have when they’re trying to explain their own incarceration to their children. When we decided to create our children’s books, we wanted to make sure that we were sensitive to tap into those issues that parents might be struggling with and to give them a voice. We know that crisis occurs within the family system. If you don’t mind, I’d like to take a moment to discuss that?

That would be good. It’s important to keep the prison family together, those on the inside and those on the outside, and especially the children. I can relate to so many things that you’re saying because I’ve interviewed many people, many parents that haven’t told their children, that have told those stories. The children that I’ve been interviewed have said that they wish that they knew the truth, that was important to them. I get what you’re saying. I understand what you’re saying. It needs to be said. Please continue, because everybody needs to hear this.

Let me establish a platform for those that may be reading and they’re trying to get a broader education on what happens to the family system when someone is arrested and subsequently incarcerated. I’m going to use a little metaphor, but I’d like to walk through this. Let’s start with the basic notion and premise that adults have a tough time dealing with arrest and subsequent incarceration. Full stop. That is a reality. Anyone that’s ever gone through this situation will recall how they were wired, how all their physical resources were stressed beyond levels of which they felt that they could deal with, but thank God, that adults have this history of which they can draw up on.

That history says, “I’ve been through some tough times before, I might be able to get through this if I have the right supports, if I have the right sense of direction, if I can find my way, so to speak, I can make it.” Children, on the other hand, and this is why we spend this quality time developing resources for children, don’t have that sense of history. They look to us as adults, to give them guidance, to be their compass, to be their North Star that says, “You’re going to be okay. You’re going to be safe. I’m not going to leave you. I’m going to make the right choices. I’m going to do what it takes to keep you safe and secure. Even though life might be a little bit rocky, I’m going to find a way for us to make it together as a family unit.”

Managing emotions is important for parents because these emotions can be translated and be projected upon their children. Share on XLet me talk about that family unit. That family unit is a family system and there’s a lot of theory that goes behind that. If I might use a metaphor of a four-legged stool, if you have a four-legged stool, it’s balanced. You can sit on it and everything steady. Imagine what happens if one of those legs were fragmented or ripped off. Now, you’ve got an unbalanced stool that you can’t sit on unless you make some configuration changes and readjustment. A three-legged stool could stand, but it requires some adjustments or reconfiguration and a little bit of rework. That’s what happens in the family.

When someone gets arrested and incarcerated, it throws the family system out of kilter. It has to find a way to readjust to new roles. It has to find a way to adjust to the grief, to the suffering, and to the loss. The family has to figure out during this stage of crisis, how to get its sea legs or get its legs back to that three-legged stool as opposed to the four-legged stool. It’s not going to just go back into balance and harmony right away without some work. There is a need for resources. There is a need for support, especially with children.

Children’s emotional health and wellbeing are largely shaped by the family. Let’s talk a little bit about how their emotional health and wellbeing are shaped by secure attachments, and it’s shaped by the family environment and possibly those supports outside of the family. When young children are born, and this will be a refresher for many people. From birth to about the first couple of years of their lives, they start to develop those essential parts of the brain that’s responsible for developing healthy relationships and secure attachments. It’s the kind of development that influences how you will begin to shape your relationships as an adult.

You’ve heard people talk about the inner child, and about how when they feel frustrated or they feel like they’re having an adult tantrum, they go right back to that place of vulnerability. That place of what it felt like to be an inner child. To nurture that during the child’s early development stage and maturity is critical and important because there’s a physiological thing or process that takes place. It’s important that the caregivers or the parents who are taking care of these children model how to solve problems, how to deal with stress and to find hope and optimism that you can get through this. It helps children to develop the efficacy and the problem-solving tools as they move forward.

The critical part of emotional development and wellbeing, maturity and development, does have a lot to do with what that child is seeing going on in the household. One of the things that we can empathize with is that parents don’t always have the tools that they need to have conversations that are age-appropriate with children. Using the tools that give them a platform to talk about arrest, especially if the child has seen the arrest, or to talk about the incarceration.

To have these tools, and to talk about how they can use a tiered approach to having conversations based on the child’s age of which that’s what our resources are designed to do, is important for caregivers and parents to have this resource to help them as they might be struggling. Our resources also are designed to give them prompts. “Little guy, I noticed that you were looking sad. You look unhappy. I feel that way, too. Let’s talk about it. Let’s talk about how we can get you back to feeling happy. Let’s talk about what steps we can take together. developing a plan.”

That’s the wonderful thing about bibliotherapy, which is the underpinning for our children’s books. Bibliotherapy simply means using books to promote healing and problem-solving within the context of your life. A book that has true bibliotherapeutic principles are the kind that an individual can see themselves in the book. They can also see the main character or characters solving problems and emulating how others in life would solve those problems.

The important property of being able to read a book and having a parent read a book is that you use this principle called distancing. What that does is it gives you a safe distance to see someone else going through a problem that might be similar to your own. It gives you a platform to talk about it, look at it from different perspectives, and actually see yourself as visualizing the steps that you could take to solve that problem. The end product of that is an action plan for the child or for the family.

I’m making it sound structured and principled, but at the end of the day, you read a book to a child about going to the jail or the prison to visit. You might point out, “Jamie went through the metal detector.” It was funny because we saw the object in his pocket. You laugh together and it’s like, “When we get ready to go through the metal detector when we go visit mom or dad, we got to make sure that you don’t have anything in your pockets like Jamie,” that kind of situation.

You can use the book as a discussion starter for your own children. We’re thrilled about the books. I want to say one last thing about the books. There’s something important about using books to discuss sensitive topics. It is important that you have a wide variety of books. Not just books on incarceration or on the pandemic. I’d love to put a plug in for the book, Hope on Mars, that discusses the pandemic. It’s important to have a wide variety of books for your children. Why? Children will develop or can develop a neuro association or psychological association with, “Every time I read a book, it’s a bad thing. I’m going to be talking about these emotionally-laden topics.”

It’s the kind of thing that you want to avoid. You want to have a good solid mix so that, one day you might read about going to the zoo and visiting, and laugh and talk about funny things. The next day, you integrate it with the idea of, “This book is a tool. This is an activity that we can use to learn some things, to learn to problem solve, to learn how to experience or prepare ourselves for new experiences, or see how other people are solving problems.”

The books should be a wide variety because you want your children to embrace the act of reading. The added bonus and benefit from doing so is the act of sitting down next to a parent, a caregiver or an educator promotes bonding. Imagine what it takes to sit next to a person that has a physical book or a digital book on their tablet, and they’re reading to the child or listening to the story together. That togetherness, that bonding promotes a sense of security, secure attachments, and in some cases, that illustrates the love for or between the parent and the child. It’s a wonderful thing. The other bonus is that children develop literacy. That’s a nice way to make sure that you’re adding to the children’s literacy skills, as well as helping them to problem-solve.

Dr. Johnson, this has been wonderful information. It’s going to help so many families because a lot of times people don’t know what to say to the children. I did have a few questions. I was wondering about the books that you have done for children that you have authored, what is the age range for those books?

Baby Star Finds “Happy” is the book about a mom being incarcerated. I will tell all parents that regardless of their age, even though this book is from birth to age five, that you can read it to children who are older. Some would say, “That’s a stretch.” How do you read to young kids that are still 6 to 9 months old? I want to remind everyone, you probably heard many people say, “I sing to my child,” “I sung to my kid when I was pregnant.” “I used to read to them while I was still carrying the child in my third trimester,” that kind of thing. You can start to read to your children before they even recognize the images or the words. Remember the added bonus of reading to your child and bonding with your child.

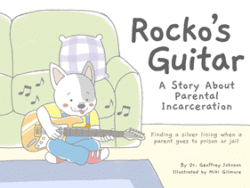

Baby Star is designed for 0 to 5. Jamie’s Big Visit is for children ten and under. Rocko’s Guitar is a book about a parent who actually didn’t tell the child the truth. Rocko is a young lad and dad is a good guitar player. Mom says, “Dad’s gone on tour,” when he disappears and goes to prison. Fast forward, a couple of pages in, you see Rocko sitting on the side of the bed saying, “How could daddy leave me without giving me a hug?” “How could he leave without saying I love you and go on this tour?” Mom thought she was doing the right thing, but you see how the child internalized it.

Rocko’s Guitar is for ages 5 to 7 or above, depending on their developmental ages. Feel free to know that you can read these books to children of any age, but understand that at various levels of their development, children begin to understand story sequences. Children in general, interpret books by their senses, sight, sound, hearing, taste, and touch. Our books, if you read them closely, you understand that we tap into the senses like the smell of cooking dinner or the smell of chocolate chip cookies. Kids relate to that.

Finding Hope on Mars is one of the latest books that I co-authored with four young children. It has to do with dealing with the pandemic and also the social unrest that’s happening within the country during 2020. The idea is that children with incarcerated parents were not only dealing with the incarceration of a parent, but they were also dealing with the piling on of the pandemic, and being pulled out of school from that safe space and support from their peers and those kinds of environments.

We wanted to make sure that we put that in our catalog to address it. It’s a wonderful story. It provides a platform for sharing ideas. That’s from ten years of age and under. For the more grown-up focus, Grandma Gracie and Toby written by Dr. Geoffrey Johnson, is for the caregivers to understand better how to connect with their children. Especially the grandmothers that may feel like they got cheated out of retirement, and here they are caring for kids again. It’s a great discussion starter for that.

Reading a book with a child promotes a sense of security and illustrates the love between a parent and a child. Share on XWhat an insight to our children. It’s going to help so many people out there. You may think that you’re alone, however, there are so many caregivers out there. There are aunts, grandparents and siblings. How do they tell their children? This information that you’re providing is so helpful and these resources are going to help them so much. I did have another question about what age should people consider telling children that a family member, a loved one is incarcerated?

That came up over and over again in our latest research study. We’re about to add this information to the books which we’re working on. There is this idea of sequencing. When we think about age-appropriate language, and even the act of reading a book to a child, sometimes you’ve got to introduce an idea, repeat the idea, and then reinforce the idea. With children, you know your children, every family is unique to their situation and circumstances. Depending on your child’s development, you may want to share information when a child is at age three.

For example, we interviewed a grandmother who had a three-year-old who witnessed the arrest of mom. The grandma felt compelled to spin the truth a little bit. I’ll use this as an opportunity to show what you probably want to avoid. She said to the child, “Mommy’s in the hospital.” That evoked all kinds of ideas. Now, the little child thinks that mommy is hurt because the child understood the concept of a hospital from cartoons.

We got to be careful that you have to sequence the information depending on their age. It might have been a better alternative to say that mommy is not coming home. Mommy is in a place called Prison. That is a place where she’s learning to do things better, differently, make better choices or something like that. You’ve got to create your own story. The important thing is to create a plan. To think about the ideas, think about the alternatives, and then decide, “This is the time of which I am going to share this information.” Perhaps you’re planning on a prison visit, a video visit, or whatever, you may want to share a little bit more information, but you have to make that decision yourself based on the uniqueness of your family.

I was wondering if you could give some age-appropriate examples, maybe for the younger children, but then also for teenagers on how to best present it to the children, and maybe some conversations that people can have so that they can help the children understand and not be traumatized. There will be some level of trauma no matter how they tell them.

Here are the three things that are important and then I’ll give you some age-appropriate tips. Number one, tell your child the truth using age-appropriate language. Don’t lie to the child because they may develop trust issues with adults later on in life. Generally, the truth is better. It’s more appropriate than what a child even imagines in their own mind, such as the example I gave you with the hospital. Tip number two, tell them their parent is in jail or prison. You don’t have to talk about the crime, just tell the truth. Tell them it is not their fault. Children have this egocentric state of mind where they believe that it might be their fault. Finally, underpin this whole conversation by letting them know and reinforcing the idea that you are there to support them, to talk to them, to check in and most importantly, to love them.

Let’s look at examples of what to say for the age range. If they’re two years and under, you could say something like, “Mommy or daddy loves you, but they have to be gone for a long time or short time,” you decide. “While they’re away, we can draw pictures to send to mommy or daddy. Grandma and others love you. We’re going to take good care of you.” The idea is to provide that safety net and reinforcement of love.

If they’re 3 to 5 years old, you might consider saying, “This is not your fault. Daddy or mommy made a mistake. Mommy or Daddy is learning how not to make mistakes again.” Clear and no lies involved. Children are learning now, because they’re at that age 3 to 5, that they’ve made some mistakes too. By the way, our stories illustrate how children have made mistakes, and they acknowledge them. Great talking points.

Twelve to 18 years old, “You’ve got a lot of reasons to be angry or mad, I understand it, I get that. It’s okay to feel that. It’s a natural response. You’re feeling sad and angry at the same time. I too, feel that way at times because I wish that things were different. Let’s talk about how you feel. Let’s sit out and have some time where we can work through these things, and then develop a plan so when you feel that you’re sad or angry, that we can talk about it. This is a safe space, and what you’re feeling is natural. By the way, as an adult, this is not your fault.”

Something important at all ages, “You’re a young adult, you’re a young teenager, and this is not your burden. You don’t have to take that burden.” I want to remind you all, sometimes in the situation, the adults feel that three-legged stool, and until they can get to that level of balance, parents may say, “You’ve got to take care of your little brother and little sister. You’ve got to help. You’ve got to be the man of the household. You’ve got to do what mom would normally do.” Cook for the kids.

We heard evidence in our research studies that young children like five years old were cooking or making sandwiches for their younger brother or sister. I want you to be careful if you’re a parent in that situation where I know that the resources in the family are a little bit strange, but make sure that you don’t cheat or deny the child the important elements of childhood. Play, to be a child, to have those teenage years as they grow up, and allow them to have fun. Do not deny them that because you’ll end up with a child who is an adult, who is introverted and bitter, or terribly extroverted, looking to fill the void in their teen years or in their childhood years with things outside of themselves, and externalize.

Externalizing could be seeking to fill the void of a relationship that never was filled during childhood. To use substance, food, alcohol, or other things to overcompensate and to fill the void, not understanding how to address it. To not have warm and secure modeled relationships with other people because you didn’t have that, it was distanced, or you felt alone as a child. There’s so much complexity when it comes to raising children.

Children can develop a psychological association reading books as a bad thing. Share on XWe, as parents, caregivers, and loving adults didn’t get the textbook on this is how you do step by step carrying out life in this unique set of circumstances because no book could give you the point by point, bullet by bullet context of how to solve every problem. The good news is that we can have these resources that help us to better have a conversation based on our unique situation and our unique circumstances. Difficult conversations are going to be difficult because they are, but you develop grit. You feel better because you learn how to solve the problem one step at a time based on the uniqueness of your family system. Most of all, based on the love that you have for children.

I hope everybody reads this, even people that don’t have somebody in their family that’s incarcerated to be prepared if and when this ever happens in their family. You provided such wonderful examples. It’s not only examples for people, but it’s also research. It’s also speaking to people and getting the information. This is going to help so many people. These are things that I know people that we’ve spoken to, that know you, that have been so grateful for the information.

Our episode with Neela, she talks about how she told her children and the things that she did, and the things she said. After she spoke with you, how she learned how to speak to her children and receive the tools and resources that she needed. This is important information. I’m glad that you shared it with everybody. The age-appropriate information is so valuable to help people. Keeping the prison family together, including the children is important. I appreciate your time talking about the children. Ways that people can tell their children, how to work with their children, it’s going to help reduce recidivism.

I know there are so many other things that we could be talking about. In this episode, we’re focusing on the children. I thank you so much. What I do at the end of these podcasts is I ask a general question. It could be about children or your other work. For people that are reading, is there something that you want to leave them with? Something that you think that’s important for them to know as they traverse this world of the prison system, whether they have a loved one that’s incarcerated. They’ve been incarcerated themselves or they’re the caregivers and taking care of children that have a loved one or a family member that’s incarcerated. Is there anything else that you’d like to share?

I’m glad that you asked and gave me the platform to share what’s on my mind. For us, as individuals and as humans, it’s time for us to dig deep and to find our own common humanity. You might say, “How does that relate to that which goes on in the prison system,” or what we refer to as the mass incarceration continuum? The thing is, we’ve got to find a way to show empathy because when we refer to them, that couldn’t happen to me, or it’s those people who are experiencing in that situation, what we do is in our mind, we set up and establish a justification for victim-blaming.

Families and children who have been affected by incarceration, if you ask them, they did not choose, nor did they want to do anything to contribute to that level of hurt, pain, and suffering. That’s not something that they set out to do. You said something important, you said you never know if it might happen to you, or this is good information in case it happens to you. God only knows that life can sometimes turn on a dime. One day, you’re having life and living normal, the next day, your whole entire world is upended.

Have compassion, and empathy, and love. For those of you who have gone through this situation, know deep down inside, it might be rough for a patch, but you will get through this, and you will adjust. You’ll be like that four-legged stool. It’s rocky, but you can figure out a way to reconfigure it, and you’ll find your balance. One day, the pain may not hurt as much as it did when it was fresh and raw, that you’ll learn how to cope and manage.

You may not ever get over it because those pains that you feel when someone you love is incarcerated can be deep. It will do one thing, and I promise you this, it’ll show you how to love deeply, how to love fully, and how to respect one another, and to embrace empathy and humanity. You’ll find yourself in this place where you got a strength that contributes to the outreach and to help other people rebuild their lives and find their humanity. Thank you for asking me that question.

Well said. Thank you so much. There are so many groups out there too, that if people are looking for support like friends and family of incarcerated persons that have online support meetings. There might be groups in your hometown where you’re living. You can look online. Again, I thank you so much.

I appreciate you and I thank you for the opportunity.

Important Links:

- DC Project Connect

- International Coalition for Children With Incarcerated Parents

- Dr. Avon Hart-Johnson – LinkedIn

- Baby Star Finds “Happy”

- Jamie’s Big Visit

- Hope on Mars

- Rocko’s Guitar

- Grandma Gracie and Toby

- https://TheFFIP.org/

About Avon Hart-Johnson

Dr. Avon Hart-Johnson is an author, researcher, and advocate. Her passion and creativity are evidenced by her deep empathy and advocacy for families affected by incarceration. She is an executive and co-founder of DC Project Connect (nonprofit 501c3). Hart-Johnson oversees DC Project Connect’s portfolio of services that support families and individuals who are criminal legal system aligned. Currently, she is training caregivers, helping professionals, and others to use bibliotherapy techniques (using books for problem solving and healing) and tailored children’s books to discuss sensitive topics such as parental incarceration.

Dr. Avon Hart-Johnson is an author, researcher, and advocate. Her passion and creativity are evidenced by her deep empathy and advocacy for families affected by incarceration. She is an executive and co-founder of DC Project Connect (nonprofit 501c3). Hart-Johnson oversees DC Project Connect’s portfolio of services that support families and individuals who are criminal legal system aligned. Currently, she is training caregivers, helping professionals, and others to use bibliotherapy techniques (using books for problem solving and healing) and tailored children’s books to discuss sensitive topics such as parental incarceration.

Leave a Reply